Bubblegum Club’s Lindi Mngxitama highlights the emerging artists reimagining the creative expression of a restless nation, from Lunga Ntila’s collage work to textile and tapestry artist Talia Ramkilawan

A groundbreaking South African magazine and agency, Bubblegum Club does the dual work of seeking out cutting-edge creators and independent artists, and providing exposure to emerging artists or collectives. In doing so, it both functions as a place to showcase new work, while also nurturing future trends. As well as a physical space Bubblegum Gallery, a multifaceted site in Johannesburg with a focus on offering developing artists the opportunity to exhibit work, their initiatives include Bubblegum Invites, a residency programme providing a series of chosen image-makers access to facilities and studio space.

Bubblegum Club joins 2021’s vibrant Dazed 100 – a part of Open To Change, a larger platform from Dazed and Converse aiming to provide a platform to underrepresented creatives. It’s all about spotlighting the cultural changemakers breaking new ground across the globe, platforming ideas that will enact radical change, and looking at what’s next for the creative industries too.

As part of the programme this year, five of the Dazed 100 cohort will explore their field, their practice, and their hopes for the future in their own article for Dazed. From open source digital archive and curatorial platform Habibi Collective to the queer NYC skate collective Glue Skateboards. This final iteration sees Lindi Mngxitama of Bubblegum Club spotlight six of the most vital artists emerging from South Africa today.

If Bubblegum Club were to win the Converse x Dazed 100 grant, they’d use the money to make manifest some of the vital work they’ve already been doing, to embolden and support South African creatives from every discipline. “We’d run initiatives that support emerging creatives in Johannesburg including a gallery, a residency programme and more,” they say.

You can explore the full 2021 Dazed 100, in partnership with Converse, and cast your vote now – stay tuned for the winners announcement soon.

Below, learn more about Lindi Mngxitama’s chosen six artists – from the evocative collages of Lunga Ntila to the traumas, culture, and identity issues unpicked by textile and tapestry artist Talia Ramkilawan, Natalie Paneng’s striking digital performance pieces, observant artist and bookstore owner Daniel Malan, ‘anti-disciplinary’ Xhanti Zwelendaba, and the expressive Ketu Meso.

"How can we think about art, aesthetics, and imagination without reducing it to a single story? How do we sit in conversation with the various H/histories, identities, memories and embodied experiences that are contained in art, aesthetics and imagination without replicating the violence of essentialism?" says Lindi. "In the same way that culture is not stagnant but rather, evolves, shape-shifts and mutates in its contact with society — so too does art and the impulse of expression moving it forward."

"I think of art as a space of communion," she continues. "A space of communion with where we have been, where we are and the possibilities of where we could go. At the dawn of a new decade, South Africa stands — still — suspended between two edges, clutched inthe hold of apartheid’s legacy while trying to birth itself into its something new."

"Questions of our shared national past, and how this past has informed our identities, our lives, and our conceptions of self continue to drive the young artists paving the way for reimagined creative expression in the country," she finishes. "For me, Natalie Paneng, Xhanti Zwelendaba, Lunga Ntila, Talia Ramkilawan, Ketu Meso, and Daniel Malan are some of the most vital young figures emerging today."

Get Off Your High Horse, Courtesy of the artist

Get Off Your High Horse, Courtesy of the artist LUNGA NTILA

I believe that things like identity, culture, and trauma are both located within time and able to traverse it. What I mean by this is that, although these things are coloured by the temporal specificity in which they occured, they also lived beyond it, how else are we able to speak of trauma as an inheritance?

These are just some of the sticky things I think of in relation to Lunga Ntila’s art. “I am attracted to the skeleton of identity, awareness, perspective and framing, as a way of understanding ideologies that govern the different facets that exist within us and around us”, Ntila told Binwe Adebayo in an interview with Nataal. I latch onto this idea of identity as having a skeleton especially in relation to African indigenous cultural and spiritual practices (isiNtu), where there is an awareness of many multiverses exiting in tandem and in contact with this enfleshed one we occupy: we carry many faces on our faces.

In this way, Ntila’s collage works move beyond the space of portraiture, almost becoming fabulated worlds within themselves, their brick and mortar pieces cut from here or torn from there. “The space of collage is something I became quickly attracted to because it takes away the need to be precise,” she tells me. “I found that I was able to express myself without being too concerned whether something looks “perfect”. I also like the aspect of being able to create multiple worlds at once, I am able to piece pieces that represent the past, present, and the future all in one.”

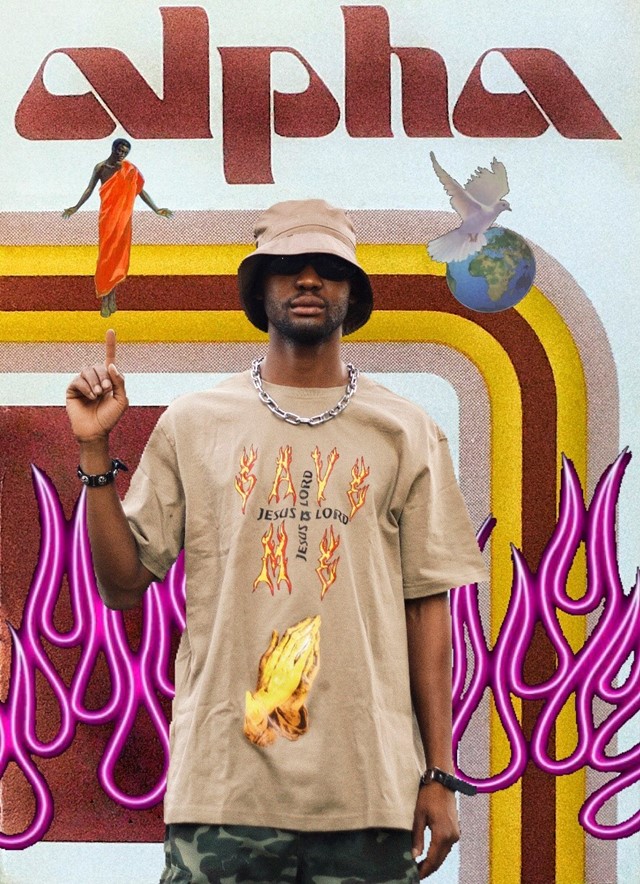

Alpha Omega, Courtesy of the artist

Alpha Omega, Courtesy of the artist KETU MESO

“Eclectic mixtures of garish early 2000s graphics and clashing Africa-specific low-res imagery give his work a maximalist, DIY panache, with his art and costumes looking as if they were cobbled together with the remnants of a bygone capitalistic utopia.” This tasty extract from an article by Ben Ilobuchi is one of the things I think about the most when it comes to the work of artist and designer Ketu Meso. That, and jazz; the unbridled riff and pleasure of its improvisation — an aesthetic of Blackness.

Coming from working on avant-garde rap duo Stiff Pap’s latest release Tuff Times, styling alongside Lebogang Ramfate, Meso’s art teases time and space. Speaking about his impulse to create he says:

“As humans we are in a constant state of becoming, and we must constantly reinvent ourselves with every stage of growth or challenge faced. The impulse to create comes from an innate, God-given desire to want to express and inspire. I would describe it as a ‘calling’, as I am a by-product of others who have inspired me to express myself. With each interaction, with each project, with each year that passes, I am growing, on an ongoing journey of self-discovery. I think that is the lifeline and desire of my practice — the need to find out about myself and my purpose through my work. Questions like: ‘who am I?’, ‘Who are we?’, ‘Where am I from?’, ‘Why am I here?’, ‘What is my purpose?’ And ‘What happens after here?’ Often pop up in my head. I think the more I grow, I am finding answers to those questions. I hope I can reflect this constant interrogation of self discovery and purpose through my work and practice.”

You’re Hot AF For An Indian Girl, Courtesy of the artist

You’re Hot AF For An Indian Girl, Courtesy of the artist TALIA RAMKILAWAN

Cape Town-born and Nelspruit-raised textile and tapestry artist Talia Ramkilawan’s work has been described as addressing “her own lived experience with South Asian identity, culture, and trauma”, by using “mixed media in order to visualise the complexity of one’s relationship to trauma using various mediums.” Speaking specifically about the relationship her work has to thinking and working through trauma, she tells me;

“Trans-generational trauma is a big theme of my practice. I am interested in how coping mechanisms — particularly in response to long-term subjugation — are passed down generations and can hinder personal fulfilment. My work attempts to break the cycle of previous behaviours by acknowledging them and actively trying to redress past wounds. My practice is centred around healing. Firstly, for myself as the experience of making the works is an act of healing, and secondly, through bringing this idea of confronting past traumas and living in one’s truth to my own community.

I want the audience to see the full scope of my lived and shared experience. Familial memories are interspersed with nude self-portraits. You’re hot AF for an Indian girl, was the first work in which I depicted myself. The title refers to the backhanded compliment often dished out to womxn of colour, which strips them of their identity by attacking their heritage. This work was a process of reclamation. By choosing to show childhood memories among some of the other more intimate moments from my present existence, I am attempting to take control of my own narrative. Ultimately, my practice is about being disruptive in a quiet space. Being disruptive doesn’t require me to be loud. I can do it in a way that feels comfortable to me.”

Ramkilawan works across various mediums, including installation, video, performance and tapestry. Her tapestry works in particular are beautifully evocative; the tactility, textures and implied softness, and the comfort and tenderness they contain almost create a space of healing to let ones’ self thaw into.

Nozulu, Mpafane, Courtesy of the artist

Nozulu, Mpafane, Courtesy of the artist XHANTI ZWELENDABA

Xhanti Zwelendaba’s work sits at the complicated and porous intersection of dominant history and metanarratives, and those smaller, more intimate narratives that speak of our inside worlds. His work is textured by the geo-political and cultural specificity of South Africa’s apartheid past and our current so-called post-apartheid society. As he shares:

“My work, at its simplest form, is a representation of the lack of words to describe some of the questions I have regarding my identity and the collective identity of Black people in South Africa. My work deals with the complexities and tensions surrounding Xhosa culture and the modern-day culture of contemporary capitalism and nationalism — and embedded within these is the legacy of colonialism and apartheid. The pursuance is largely spurred on by having to balance between these cultural paradigms, often simultaneously.”

Currently completing his MFA at Wits University, Johannesburg, Zwelendaba’s research is focused on Black representation in media and television. He investigates the ways in which this representation has shaped, and continues to shape Black identity, as well as how Black people receive each other and are received by other communities. Although he works across mediums – including print-making, sculpture and even performance — Zwelendaba thinks of himself as an anti-disciplinary, rather than multi-disciplinary, artist. In his words:

“I’ve always expressed myself as an anti-disciplinary artist, meaning I don’t let the ‘different mediums’ dictate what I make, but rather, I give my best attempt at representing my ideas through the medium it translates best in. The medium also holds a significant part of my creating, as each object and material holds its own meanings outside of art, which plays an integral part in the meaning and understanding of the artwork and its concepts. My favourite — and most pleasurable — materials and objects to work with are objects that hold significant meaning within historical and contemporary Black culture. Intervening with these objects and seeing what they can exist as outside of domestic spaces always excites me.”

Niceatopia, Courtesy of the artist

Niceatopia, Courtesy of the artist NATALIE PANENG

For me the work of the self-described “movie character and world builder” Natalie Paneng (NATALIE PNG) who, according to her Instagram bio, “just wants to be big in Japan”, calls to mind that of writer and curator Legacy Russell, and in particular Russell’s book Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. As Paneng shares with me;

I enjoyed the kind of limitlessness that the internet offered as a platform. A space where I didn’t have to follow the same rules and etiquette IRL. It allowed me to explore and contribute freely. I could take up some space and just decide on how I would be present. The Internet first felt like an empty apartment which I could dress up however I wanted — and then live in that reality. It didn’t feel like my actions had any consequences (I'm aware that they do). The digital sphere felt like a tangible space in which I could imagine and then share the outputs of this virtual-dream-world. It also offered me inspiration and knowledge, so while I was playing, I was also getting informed about how it's an extension of our physical life. Getting influenced and living in reality but building a universe online.

Similarly, in the introduction to Glitch Feminism Russell writes, “…online I could be whatever I wanted. And so my twelve-year old self became sixteen, became twenty, became seventy. I aged. I died. Through this storytelling and shapeshifting, I was resurrected.”

Through her art and practice, Paneng resurrects herself in digital spheres. Detaching her body from its restraints and scrambling them up in ecstasy, for her evocative play is a constant companion, from her vlog Hello Nice, to her digital performance pieces.

“Play is political because it is a rejection of the rules and a mode of navigation and exploration. I use play to inform me and as a tool to move away from hard limitations. My art has been a lens which gave me access to see myself as well as put effort into how I am represented (and perhaps for others too),” she tells me. “Through my work and play, I have extended my idea of self as well as worlds I want to create and live in. My main desire is to make these worlds, characters. and feelings tangible, both online and IRL.”

Jozi Spaza, Courtesy of the artist

Jozi Spaza, Courtesy of the artist DANIEL MALAN

“Daniel Malan is an artist and designer who draws, takes photographs, and makes short videos. He also runs Hot Days Cool Books, a bookstore that focuses on art and design in an African context.” — a pretty simple introduction to an artist whose art and practice is anything but.

Daniel and I had the pleasure of meeting in person,on a cold but sunlit autumn morning while he was down in Joburg for his exhibition walkabout at The Gallery. We had planned to speak about his work but instead it became a sprawling conversation ranging from the importance of flowers, longing for home while trying to find roots living abroad, and getting to ignore things for a while.

Speaking about art education, Malan shared this idea during our conversation. “It breaks people down and you have to build yourself back up again, and that’s an important process of making art, and I understand why it’s necessary, but I think there are better ways of schooling that exist. I understand that like maybe seven out of the 60 kids in your class will be thriving by the time they finish but you have to find a compassionate system that helps (everyone else). ”I think this sentiment also says something about how he approaches his own art and thinks about its relationship with the world.

Daniel’s art is very much rooted in external worlds, sitting in observation of them and capturing a moment where mundane magic happens. “When I say I like Joburg, that’s because I walk through Cape Town everyday,” he says. “If I’m stuck in town, I’ll walk home and it’ll take me 40 minutes but if I see one photo, it’ll be worth it. I like being in the world and spotting things and making connections or seeing people in suits on motorbikes — it sparks joy in me.”

Through beautifully composed photographs and large-scale chalk drawings, many of which are filled to the edges with movement that calls to mind the style of the Russian painter Kandinsky as Malan absorbs the world around him and interprets it.