‘When clients and casting ask for an Indonesian model and I submit my portfolio I usually get the same answer: we actually want an Asian-looking model’

Growing up biracial in Malaysia, model Hikma was often bullied for being different. Constantly teased for being plus-size, for her dark skin and her curls, she started wearing hijab just to stop people looking at and touching her hair.

In Vietnam, Huỳnh Tiên, who is of Cameroonian and Vietnamese descent, faced similar comments as a child. “I remember to this day one girl, when I was around five or six years old, said to me: ‘Ah you are so ugly and Black, why don’t you go back to the forest,’” she says. “After that I always doubted myself and thought I am ugly. I was the black swan in a pond of white shimmering ‘real’ swans.”

Experiences such as these are all too common in Southeast Asia, where colourism is deeply entrenched in the culture and continues to flourish. Originally tied to a system of hierarchy where darker complexions often denoted manual labour done under the hot sun, colourism was then only strengthened by colonial rule. “In many societies, the preference for light skin has probably occurred for hundreds, if not thousands of years,” says Nikki Khanna, associate professor of sociology at the University of Vermont and author of Whiter. “Though European colonialism undoubtedly exacerbated the problem.”

Colourism rears its ugly head in Southeast Asia in various forms – whether it’s shown through the multitude of skin whitening billboards that pop up on every corner or the fact that many Southeast Asian entertainment figures are lighter-skinned or mixed race. “People with dark skin, non-thin bodies, and or those that do not have objectively attractive features AKA Eurocentric features are severely underrepresented in media [in Southeast Asia], especially through a creative lens,” says photographer Catherhea Potjanaporn, who has coordinated and shot photo series aimed at spotlighting minority groups within Malaysia.

Asia made up over 50 percent of the overall global sales of the $8.3 billion skin whitening industry, a 2018 report found. The industry is projected to reach nearly $12 billion globally by 2026. “These products wouldn’t be so marketable if skin lightening was merely a fringe issue,” says Khanna. “They capitalise off of cultural norms that venerate whiteness and light skin, though they also perpetuate these norms through their products and advertising.”

For biracial people in Southeast Asia, the issue of colourism is further complicated by the compounding aspect of race. More specifically for those of Black descent, as they face the stigma of being both mixed-race and partially Black, explains Khanna. Here, 15 models and creatives of Afro-Asian and Indigenous descent from across Southeast Asia discuss their experiences with colourism within their respective countries.

Courtesy of Iman Mohamed Osman

Courtesy of Iman Mohamed OsmanIman Mohamed Osman, Malaysian and Sudanese

“Growing up in Malaysia I encountered comments about my skintone, my curly hair and how pudgy I looked. In the early years of my childhood and teenage years, it was hard because I did not feel accepted. I grew up with a lot of fear and low self-confidence. Both colourism and discrimination are universal problems. And when people pretend that these problems do not exist, that’s when issues start to arise.

One day I saw comments on the internet about me representing a brand for a campaign called Beauty Beyond colour. This campaign was to promote awareness of skin colour and that everyone is beautiful, however these comments mentioned how they could have just hired a Malaysian model instead of someone who is dark. They said, “What are they selling? Charcoal products.” Imagine the young girls and women reading these comments. What are we teaching them? That they are not enough? That they don’t belong in society?

This is why I am super proud to be on a magazine cover [Harper's Bazaar Malaysia] representing many other dark skin girls out there. We’re all capable of so many things. We dark skin girls are one in a million. I want to tell them all to keep doing you, keep shining! And to be proud that you’re a melanin goddess.” – Iman Mohamed Osman, model

Courtesy of Hikma

Courtesy of HikmaHikma, Ghanaian and Malaysian

“Growing up biracial in Malaysia wasn’t a great experience as I was constantly verbally bullied. Most Malaysians find it hard to accept people who don’t fit into their category of “normal”. I was questioned many times by people around me because I had a fair-skinned mother. I was teased for being plus-size, having dark skin and curly hair to the point I started wearing hijab because I hated people looking and wanting to touch my hair. It wasn’t a good experience growing up in Malaysia but thankfully I was blessed with open-minded friends who were always there for me and who didn’t view me as someone “different”.

Brands need to stop promoting white and fair-skinned people as the only form of beauty there is in this world because that kind of mindset is stuck in the minds of most Malaysians. Parents need to firmly educate themselves to not be racist because children are not born racist. They only learn and follow what their parents do and say. Changes won’t happen overnight but Malaysians need to start educating themselves and accepting that there is beauty in everyone no matter their background or what colour their skin is because at the end of the day, we are humans and most importantly, we are Malaysians.” – Hikma, model

Courtesy of Danial Hogan

Courtesy of Danial HoganDanial Hogan, Nigerian and Malaysian

“Growing up biracial in Malaysia has definitely had some downsides to it, especially as a child. Children don’t have the capacity to understand the impact of their actions and are mostly guided by their parent’s teachings. I experienced colourism and discrimination in school, with the students and teachers, and when I tried to mingle around at the park as a kid. As I grew older, I accepted [my darker skin tone] as part of my identity and kinda decided to be proud of it.

Being a part of the photo series ‘Dark Is' made me feel like I was a part of a very powerful movement. Despite being in a multiracial country, the locals often have prejudiced views towards people with darker skin. So being a part of something that spreads awareness and was aimed to educate was very inspiring.” – Danial Hogan, model

Photography Felix Schickel Photography

Photography Felix Schickel PhotographyHuỳnh Thị Cẩm Tiên, Cameroonian and Vietnamese

“Colourism and being of African descent definitely has shaped my life in both good and bad ways. I remember to this day one girl, when I was around five or six years old, said to me: ‘Ah you are so ugly and black, why don’t you go back to the forest.’ Of course that was just childsplay and now, thinking back on it I can pretty much laugh it off. But when I was younger, well that is a different story. After that I think until the age of 16, 17 I always doubted myself and thought I am ugly. I was the black swan in a pond of white shimmering ‘real’ swans. The odd one out, not belonging but belonging, if you know what I mean. Only after my best friend told me that I am actually pretty and secretly signed me up for a beauty contest in my village, which I won, I realised that hey maybe I’m not too bad looking.

Consequently, this discriminatory aspect of the Vietnamese culture towards people of colour is what I tried to overcome all my life. I am proud of my skin. I love my skin and colour. It is what defines me and makes me who I am. And I love both my Vietnamese/ Cameroonian heritage and I try to embrace that everyday.” – Huỳnh Thị Cẩm Tiên AKA Nahfeh Dohmatob, model and fashion designer

Courtesy of Malyneth Nin

Courtesy of Malyneth NinMalyneth Nin, African and Cambodian

“This is definitely an Asian issue but I think in the past due to the multiple mixing of people in Cambodia throughout the ages, dark skin was not really a problem. The issue of colourism is coming from the more recent world of fashion in Asia where all the boys and girls from the countryside want to look like their “idols” from the main cities. Even if it means using cheap and dangerous products to whiten themselves.This is something I really want to fight against by educating the younger generation that beauty comes from within. My main struggles started during my high school years a teen. Many of the other kids would point out my differences (my darker skin and curly hair). After that I began to utilise my differences as a uniqueness and therefore turned what was once my ‘problem’ into a quality.

The beginning of my time at Miss Universe Cambodia [Malyneth was Cambodia’s first Black Miss Universe contestant] was not easy as I was the only dark-skinned representative of my country but African nations have had a close history with Cambodia as they've helped in the past during the Cambodian civil war, along with other UN forces and its peacekeepers. So I have come to fully embrace this aspect of my racial identity and I felt like a proud representative of my country.” Malyneth Nin, model

Photography Morgan Sizlak

Photography Morgan SizlakAlexa Lourdy, Nigerian and Indonesian

“I am not going to lie, it is not easy to grow up in Indonesia being a biracial kid. I’ve experienced some harsh bullying and colourism. I think it’s because of a lack of education and sometimes it’s because of pure racism. But you know even nowadays some people still call me with the n-word, shockingly people that I believe are educated enough working in the fashion industry. I believe all the discrimination and bullying I’ve experienced about my skin tone and my curly hair has actually strengthened me and pushed me to be more confident and I now use it as my power.

I can say Indonesia’s fashion market has always been open to diversity. Especially with all the movements of the Black Lives Matter, self love and diversity. Even though there are still some incidents of light skinned models getting heavily darkened on photoshop, or using black hairstyles for the sake of ‘art’, which is very wrong. Though I hope this change is not only just performative activism but a genuine acceptance that dark skinned people of colour also need representation in the fashion industry.” – Alexa Lourdy, model

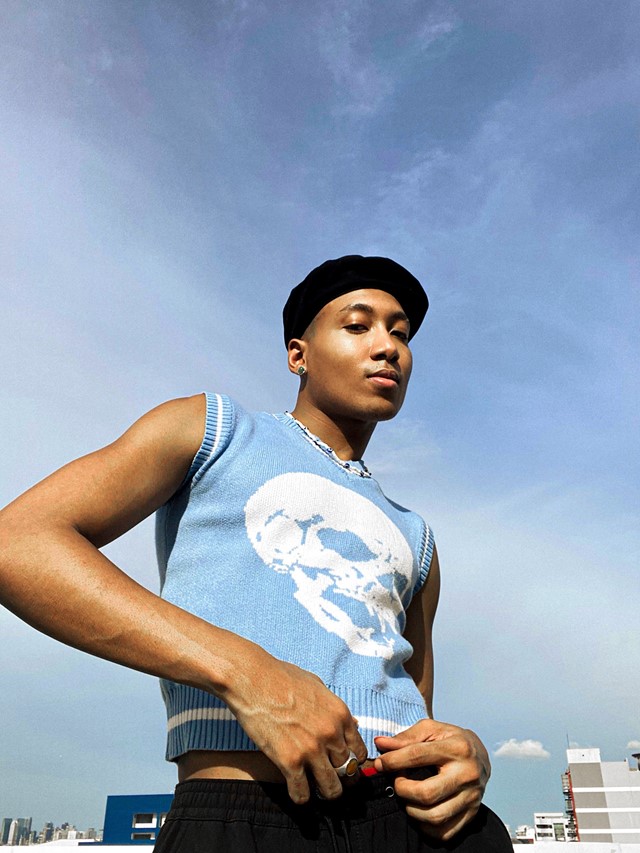

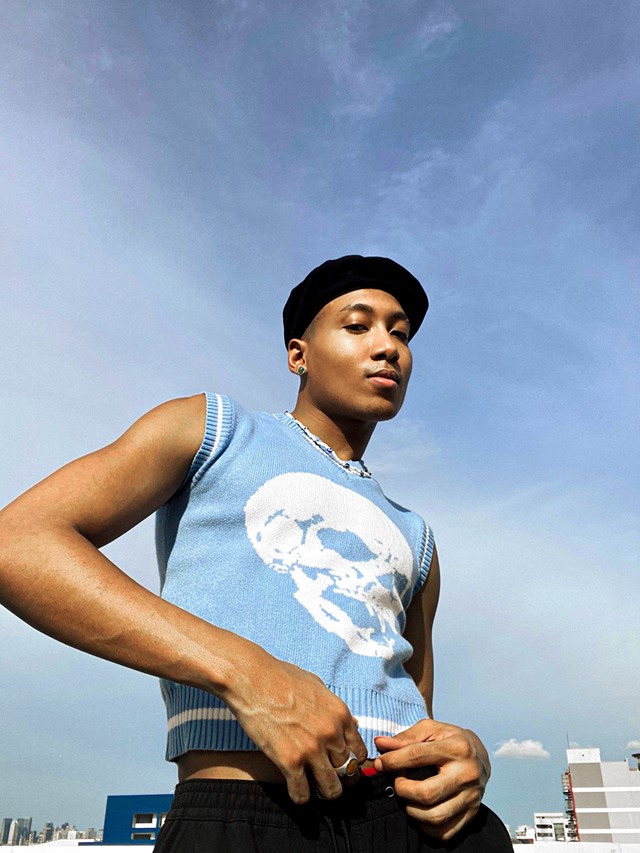

Courtesy of Atta Nyarko

Courtesy of Atta NyarkoAtta Nyarko, Ghanaian and Indonesian

“I’ve faced discrimination all my life, in school, while meeting new people, walking out in public, social media, and even in “high class” environments, but these weren’t blatant upfront ways of discrimination, these were more subtle and nuanced. The way people talk to me compared to others, the way people look at me, and the way people treat or handle me all had racist innuendos. It gets tiring at times but my parents taught me to be better and turn the other cheek in those types of situations. Although I have gotten emotional on multiple occasions because it was just too bad.

I was literally the only African kid I knew growing up so my Dad was obviously the strongest support I had and soon enough I strived to be like him at times as he was the only other colored man I knew. The lack of representation led me to look up to other great people of colour I saw on TV or the internet like Muhammad Ali, Will Smith, Bob Marley, Michael Jackson and so on, hence my sense of style and love for art and media. I never took any of the discrimination personally as I knew it was due to the lack of education and social awareness people had, which I hope gets better in the coming future here in Indonesia.” – Atta Nyarko, model

Photography Ikmal Awfar from Persona Management

Photography Ikmal Awfar from Persona ManagementBraxton Kamga Bravo, Cameroonian and Indonesian

“I have actually felt quite comfortable living here in Indonesia as a mixed-race girl. But of course, I've been in situations where I get discriminated against. When I was in elementary school some of the students would be extremely rude. I would get bullied because of my skin colour and my hair. I got bullied for being Black because they think that Black is ugly and therefore being Black is something that is shameful. However, many people here are also very kind too.

As I have grown older I have realised that my skin colour and curly hair are the best gifts from God. Especially here in Indonesia some people might see it as something unique, and being unique means being different. Some people might be scared to be different because they think it’s something bad but to me being different is something that I feel proud of.” – Braxton Kamga Bravo, model

Courtesy of Peace Jemima

Courtesy of Peace JemimaPeace Jemima, Nigerian and Indonesian

“Growing up biracial in Indonesia affects everything in my life. I’ve experienced discrimination and I felt alienated during most of my childhood especially in middle school. Every single school I’ve been to I’ve always been the only black student, and so far I’ve only ever had one black teacher. I remember he would always have my back whenever other kids would make fun of my skin colour. Even to this day, I could walk out of my house with my fro out and kids sometimes even adults would still point their fingers and laugh at me. Personally, I’ve gotten used to it, because wearing my hair in its natural form is one of the many ways of expressing my pride in being Black. And all of the bullying I experienced has made me more confident today.

People’s mindsets are slowly evolving. I had a friend that whenever I would land a project that I was excited about, would constantly remind me, “You know you only got the job because you’re Black right?” At first, I was offended, but now that I think about it, it’s kind of true. I do realise that sometimes I get jobs because of my Blackness and I’m proud of it. Although I often feel like the token Black girl, this is only just another step closer to the acceptance of dark skin tones throughout Indonesia.” – Peace Jemima, model

Courtesy of Monalisa Sembor

Courtesy of Monalisa SemborMonalisa Sembor, Indigenous Papuan and Indonesian

“My father is from Papua and from the Moor tribe in Nabire, and my mother is from South Sulawesi and the Toraja tribe. I was born and raised in Wamena Papua and left to go to college in Yogyakarta. When I moved out of the island of Papua, I felt very different because I physically became a minority in Yogyakarta. My skin colour and hair type made me feel insecure and I avoided many friends who I thought were the beauty ideal depicted in the media or in the advertising world in Indonesia. But as time went on I realised that I have my own unique look that many women in Indonesia do not have. I was born dark skinned and I am proud of it. I love my skin colour and I love my curls.

There are so many women from Papua who have talents like me in the world of modeling, but we are rarely used because our physique is not the standard of what the Indonesian modeling world desires. We are sometimes accepted in a project but only as a supporting talent and rarely are women from eastern Indonesia the main talents. But I believe that what I am doing by continuing to promote Papuan women through my social media in the future will help make more and more Papuan women make it in the world of modeling, acting and advertising.” – Monalisa Sembor, model & influencer

Photography Maya David

Photography Maya DavidYona Miagan, Indigenous Papuan

“As a Papuan model in Indonesia, it has been both challenging and exciting at the same time. When clients and casting ask for an Indonesian model and I submit my portfolio I usually get the same answer: ‘We are actually looking for an Asian looking model’. It was rough and a little upsetting in the beginning but I eventually turned this ‘disadvantage’ into my strength. In the future I hope I can inspire other Papuan women to be proud of themselves and to be confident in their own skin.” – Yona Miagan, model

Courtesy of Annisa Dabex

Courtesy of Annisa DabexAnnisa Dabex, Indigenous Papuan and Indonesian

“Back when I was growing up, I used to think I was not pretty enough because of the way I looked and that I was far from the beauty standard at that time. Everything in TV, magazines, and other media was portraying that lighter skin and straight hair was beautiful. I straighten my hair for years and used whitening beauty products just to fit in. – Annisa Dabex, model

I got bullied by other kids when I was in elementary school because I looked different and people didn’t commonly see someone like myself. This made me feel insecure and I felt self-hatred too at that time because of the way I looked. It was a bummer back then as no one acknowledged that the beauty standard could have a negative impact on the people who didn’t fit in with that perception of beauty. Currently, people here in Indonesia are working on those mistakes by learning to acknowledge the existence of the diverse beauty of the people, more than just favouring those with lighter skin tones or straight hair, which I’m happy about.”

Courtesy of Kahlea Belonia

Courtesy of Kahlea BeloniaKahlea Belonia, Filipino and African-American

“When my family and I first moved to the Philippines, I was very young. I knew I was different, and just being in a school where I was the only ‘Black kid’ was emotionally and mentally confusing. I would get bullied because I looked different, and of course, as a kid, you’re very sensitive. My childhood friends made a big impact on my life, they helped me realise the importance of being different. I grew up with a bigger mindset, I became invincible, and I started seeing my differences as benefits. I had a very religious family, and I was blessed to be raised by them. I have come to the conclusion that everything happens for a reason.

The proudest moment of my career is when I finally realised how comfortable I am in my skin. I am different, I will always be different, and I see that as a good thing.” – Kahlea Belonia, model & artist

Courtesy of MJ Brown

Courtesy of MJ BrownMJ Brown, Filipino and African-American

“At first, it was really hard because I grew up lacking confidence. It was especially tough for me when people would make fun of me because of my skin colour. They usually call me ‘Aeta’, an Indigenous tribe of people here in the Philippines. And then people would always tell me I should use glutathione or other whitening products so I would look prettier.

When it comes to my skin colour and my hair type, clients often don’t pick me because of it. As for my cleft, it is one of my [positive] assets because I’m quite different from the other models and I believe it gives me a unique look.” – MJ Brown, model

Courtesy of Chumason Njigha

Courtesy of Chumason NjighaChumason Njigha, Nigerian and Filipino

“Colorism in the media definitely gave me low self-esteem. I never really considered myself to be someone considered ‘good-looking’ or ‘attractive’. There was always an underlying message in the media that the darker your skin was, the less desirable you were. Skin colour became an indicator of a person’s status in the community. Growing up, I felt like the only thing Black people could be successful in this country would be playing sports. People would always associate me with Black basketball players because Black people were not known for anything else in the Philippines.

I am still very young and quite ambitious, so I’m really hoping to get more opportunities to model here in the country and abroad. I really do want to help inspire other black or darker-skinned Filipinos. It’s time to appreciate all skin tones.” – Chumason Njigha, model and athlete