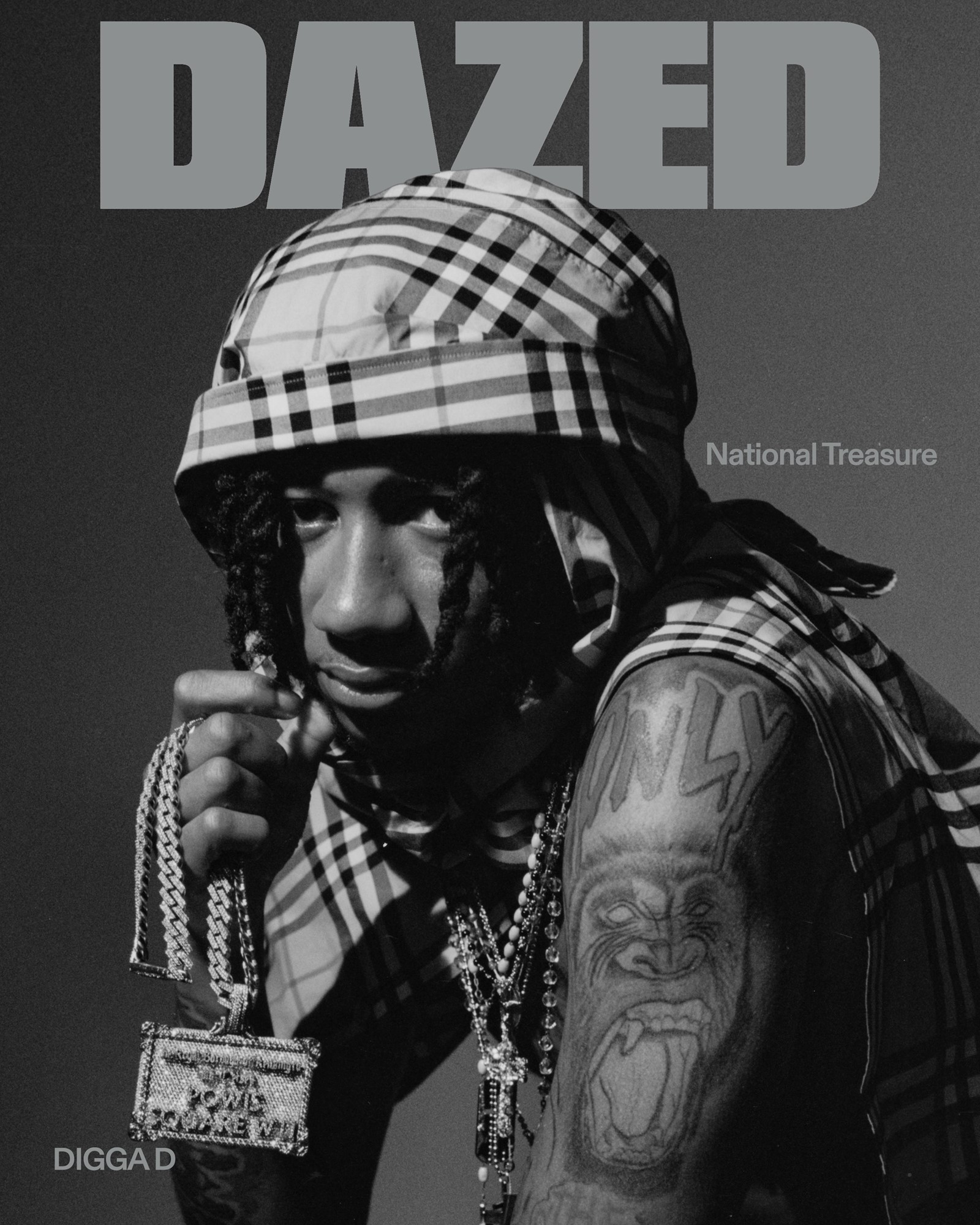

Taken from the summer 2023 issue of Dazed. You can buy a copy of our latest issue here.

It will take Digga D about 20 minutes, give or take, to warm up to me. “Don’t take it personally,” says his publicist, remarking that he is, in general, a man of few words – though being clever and nasty and evocative with them is how he made a name, how his bread is buttered. When we first speak he’s in Trinidad, where the weather is so unrelentingly hot that, even in the shade of a sapodilla, the energy expended by a long conversation can make you feel light-headed. And so he is curt. (“It makes me money,” he says of his motivations.) He is evasive. (“When it started making me money,” of when he realised he was good.) He is brushing his shoulder-length twists from his face and moving from the porch to a room inside, then shifting to another, equally airless room, searching for a comfort that is likely to elude him. He is answering my questions vaguely, or with a handful of words, and then punctuating his responses with, “You get me?” Often, I do not.

Throughout our first conversation, it appears as if he’d rather be dozing on a hammock beneath the Caribbean sun, which seems the obvious choice over speaking to a stranger with a notepad who is asking you to take stock of your life. Nostalgia doesn’t come easily for those shackled to their worst mistakes. And so it is unsurprising when the software that transcribes our conversation tells me afterwards that I’ve somehow done 60 per cent of the talking, despite being the appointed reporter in the situation. For a moment at the beginning of our interview, it feels as if we’ve traded roles. Digga is asking the questions. He wants to know what I’m planning to write. He wants to know if I mean to talk about the music he’s been making, or if I mean to clear the air (which has for years been thick with tabloid panic). If a side-eye could speak, it would be Digga D saying, “Which one is it?” His lawyer of five years tells me he is distrustful of journalists. His publicist tells me 90% of the interviews he does are with uniformed men who want to recall him to prison. Men who believe his music should be targeted with terrorism legislation. Men who will be reading this profile for reasons besides entertainment.

At 22 years old, Digga D, born Rhys Herbert, is already one of the brightest stars in the UK music scene. He’s released three mixtapes in as many years, and his latest offering, Noughty By Nature, debuted at number one on the album charts last year. He’s won plaques for several singles on the Top 40, and accrues millions of views on the music videos he posts to YouTube – that is, the ones that haven’t been scrubbed from the site by Project Alpha, an ‘intelligence-gathering initiative’ funded by the Home Office. He’s signed to a record label that he founded himself, called Black Money Records, which he says he formed in response to “an industry renowned for exploiting artists from my world”. And he’s made fans in the likes of Drake, Stormzy, the late Pop Smoke and... Zac Efron. These days, it’s hard to talk about the crowded new vanguard of drill music, about K-Trap and Headie One and Unknown T, without also, ultimately, talking about Digga D.

Music critics tend to jubilantly credit him as a pioneer of drill, and he stands apart from his class in lyrical ability. Digga’s flow, like his personality, is alternately brazen and truculent, laidback and unflinching. His imagery is clever. Even extended, naturalistic musings on the brutality of street life are occasionally pierced by cheerful ad-libs (glee! woi! bluuwuu!), so that stories of innocence disturbed and forfeited, lives taken and lost, are punctured by the reminder of our witness’s youth, and that he’s maintained his sense of humour despite everything he’s seen. There was a time when he seemed relatively proud to be included in the pantheon of drill luminaries, when he would say things to interviewers like, “Other people made drill, I just took it to a place it’s never been before.” But Digga has gradually adopted a reluctant stance towards the genre upon which he built his riches and his fame. It’s an ambivalence that extends beyond the classic, cliched contempt for one’s vintage material, a defiant wariness that coalesces on a bunch of new tracks he plays me. “I don’t like drill no more, it’s tired / Can’t bear man liars / If you lot saw my priors / You’d call me Michael Myers,” he raps coolly on one, over what sounds like a warbled sitar. Incidentally, it’s one of the few drill songs he’s been working on lately, and Digga laughs mischievously when I bring it up, clearly amused, in an almost childlike way, by the minor insolence involved in his own winking dismissal. “I’m not someone that likes to follow fashions,” he says, shrugging. “It doesn’t mean I’m rebellious, or I like to break rules. It just means that if I see too many people doing one thing, I go the opposite way.”

Digga’s new music features some more adventurous beat selection than some of his past projects have, but the adherence to a more classic strain of 2000s hip hop goes deeper than a love for the American greats, or the simple fact of maturation.“I don’t feel like I’ve outgrown drill, necessarily,” he says. “I don’t think that drill is something that can be outgrown, because there are people who are, like, 30 years old making drill songs, people who still have something to say. I might be a little frustrated with drill, though, because people” – and here he’s talking about people without craft, people who coast on gimmick – “have taken the genre and made it into a comedy. It’s like boxing,” he says. “With the fake fights and stuff – it’s taking away from what boxing actually is. You have to be talented to fight. Now, people are arguing online, training for two weeks, and then getting in the boxing ring and calling it boxing. It is, but it’s not.”

Besides comedy, the last few years have seen the genre abstracted into a reason for mass hysteria, into political roundtables and courtroom evidence, into amoral contagion and “the soundtrack for London’s murders”. Drill has come to represent a host of pearl-clutching fears, as all global Black music eventually does. And because it often archives the bleakness and deprivation of the inner-city life that birthed it – where more than a decade of government austerity measures have decimated social services and hiked up knife crime among youth – drill has inevitably been blamed for inciting the violence it strains to record. “It’s essentially discussed as a front for criminal gangs, indeed as the embodiment of criminality,” says Dr Lambros Fatsis, a senior lecturer at the University of Brighton who researches Black music subcultures and acts as an expert witness in court cases involving the use of rap as evidence. “We discuss drill as a source of concern, as what I describe as being aesthetically out of tune, culturally out of place, and politically out of order.” It’s a conversation that has, throughout history, plagiarised its own more annoying, ahistorical conclusions about the relationship between culture and violence, a philosophical ouroboros of conservative fear. The horse is long-dead but not quite buried: is the brutality native to some factions of rap music proof of art imitating life, or is it the other way around?

“There’s a lot of things that are violent: rock music, GTA, Kill Bill, Anne Frank’s diary – we don’t ban those,” says Digga. “But the younger generation made drill global, and it’s Black-owned. It’s not fair to say that we’re causing violence. We’re just talking about our lives. There might be some violence in there. But that’s what we grew up on.”

Still, nearly 20 years after Lethal Bizzle’s “Pow!” was banned from radio airwaves and the club circuit alike, Digga D and his cohort have become the metaphorical battleground upon which this war is being fought. In 2018, when he was 18, Digga was sentenced to a year in prison for conspiracy to commit violent disorder. The police stopped him and his friends, with whom he made music as the drill group 1011, and found them carrying four knives and two baseball bats. They claimed they were on their way to film a music video; the police said they were on their way to attack a rival gang. They pled guilty in court, where prosecutors submitted their music videos as evidence. In English courtrooms, drill is considered ‘gang-related music’, and so heads of gang units and cosplaying music critics are called upon to translate and interpret lyrics for everyone else. (Everything is taken literally, and the implication is that rappers lack fictional imagination.) The Met applied to have the group banned from making music that “references violence”, and, in what was reported as an unprecedented decision, the judge granted it.

“It’s upsetting, because without Harrow Club, I wouldn’t be who I am. You never know what chances they’re taking away from these kids”

Digga became one of the first artists to be assigned a criminal behaviour order that limits who he associates with, where he goes and what he says in his music. He has to turn in his lyric sheets to the police 24 hours before releasing any music. There are songs he can no longer perform. The order is complex and extensive and, if he breaches its conditions, he can be recalled to jail. This happened three times before he turned 20. It’s one of the main reasons, I later learn, that he’s so laconic in our first conversation: his lawyer is not present to counsel him on which parts of his own history he’s legally allowed to discuss. Until 2025, when the order expires, his adolescence is considered too violent to rap about. And he has to mind what he says in his interviews. In this way his life does not totally belong to him. His songs are riddled with imposed silences.

He’s much more at ease the next time we speak, a week after our first conversation. His lawyer, Cecilia Goodwin, is on the call with us, as is his publicist, Rachel, and so the uncertainty that once marred his candour has been replaced, at least partially, with affability and charm. There’s a stillness about him, too, that feels more solid this time around, a kind of serenity one may expect from someone far older than he is. I get the sense that this mode of being is far more natural to him. “I’m back in London,” he says. I am sitting, once again, in front of a laptop screen, and Digga is seated at a table on what might be a bistro patio, asking, with a politeness reminiscent of a child seeking permission, “Is it OK if I eat on this?” He scarfs down a handful of fries and sips at his drink. When his speech becomes muffled and he identifies the root of the problem, which is that his braids are covering the mic on his AirPods, he says, “Wowwwww.” Someone says, “That’s discrimination.” Everyone laughs.

Digga does not strike me as someone who is at all sentimental, but he is more willing now to talk about the past. Despite the money and the well-worn passport, he says he hasn’t felt free since he was a child. Back then, things were simpler. He didn’t have any responsibilities, except going to church with his mother on Sundays. (He doesn’t go to any more, because it doesn’t feel comfortable or welcoming to him, but his mother still sends him YouTube streams of services every weekend, which he admits to watching “sometimes”.) Back then, he had nothing to avoid or worry about. He was born in Ladbroke Grove but has also lived in nearby Harrow Road and Notting Hill where, in the summers, he could see the Carnival in the street from his window. The riddims and the din of celebration would spill into his home. His parents are both West Indian, from Jamaica and Barbados, and they used to take him down to the soundsystems that blared reggae into the crowded streets, where the bass bore itself into his body. Reggae and dancehall were some of his earliest experiences with music. He’s quick to note the extent to which Jamaica has influenced British culture writ-large, “even down to the language. You have Albanians talking about going to their yaad, and the whole country saying wagwan without knowing where they got it from.” If he ever chose to move out of London, he is sure he would go either to the Caribbean – maybe to Jamaica – or Miami.

But for now he is in London, sifting through his memories. “I started going to Harrow Club when I was, like, 12,” he says, recalling days spent playing football at the youth club. It used to be a church, and so the building has soaring ceilings with exposed beams and ornate period windows that look out towards Latimer Road. The club was formed in 1883 as a charity called the Harrow Mission, in response to the needs of what first Missioner William Law described as a “forlorn, neglected and desolate” area. Today, reports have identified high levels of post-traumatic stress disorder among people who live locally, and life expectancy, according to the club website, is 12 years longer in the richest ward of Kensington and Chelsea than it is in the poorest. “That time moulded me into who I am today,” Digga continues. “The sports hall upstairs, the studio downstairs. The music workshops. They used to take us on day trips – paintballing, stuff like that. Lots of different activities. I’m an only child. I couldn’t go home and play PlayStation with my brothers. I didn’t have that. So that’s where I would go.”

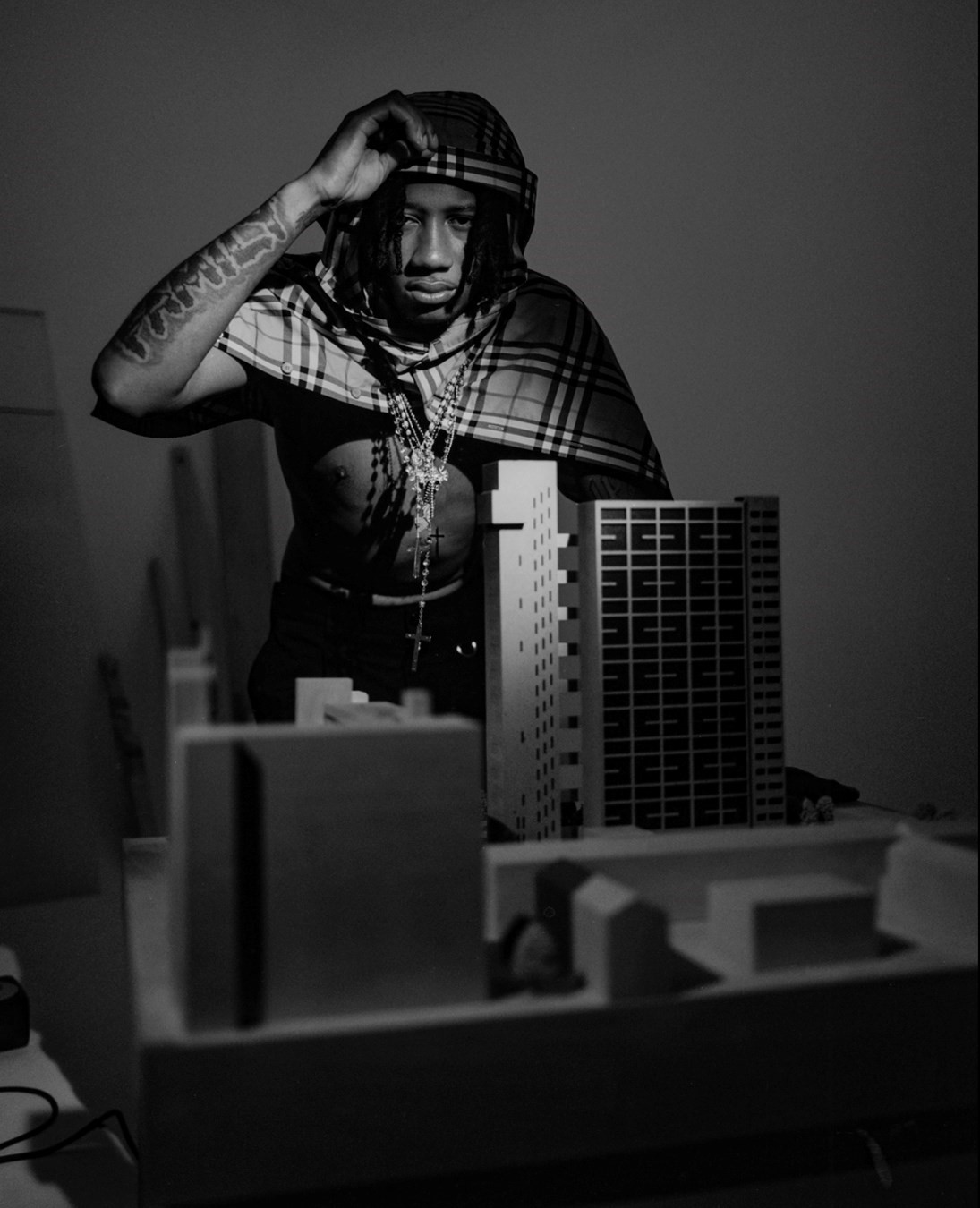

Ladbroke Grove is a trip, a trompe l’oeil. It wears its stratification like a jacket. The area has a historical reputation for poverty and decay, but there are million-pound Victorian townhouses slotted next to crowded council flats, the fallout, some say, of a development blacklisting that followed the riots of 1958. In 2017, Grenfell Tower, a housing project metres away from Harrow Club, caught fire and burned for 60 hours, killing 72 people. Residents had been raising concerns about fire safety for years. The area has the highest rate of permanent exclusion in all of London, and a quarter of the children who live there are below the poverty line. Some of the most expensive homes in the city are there, grand white stucco houses with terraces that overlook sprawling, bucolic gardens. “You’ll see a matte-black Bentley driving past someone who’s on the side of the street struggling, trying to steal the smallest thing,” says Digga. “And then expensive five-star restaurants.” Ladbroke Grove has a reputation, too, as a haven for artists, musicians and other kinds of misfits. Eric Clapton formed Cream while he was living there in the 60s. And Jimi Hendrix died of an overdose at the Samarkand Hotel, a 15-minute walk from the studio where Digga started recording songs.

It was in the mid-2010s that he and his friends began messing around with music after school at the youth club. It started out as a joke, as many things that become quite serious do. They were just passing the time, rapping over drill beats. They started uploading their songs to SoundCloud as 1011. When he was 14, Digga’s grandmother, with whom he was living at the time, died, and soon after he was expelled from school for selling weed. “And that’s where all of that school stuff stopped,” he raps on the intro to Noughty by Nature. Black Caribbean students in English schools are up to six times more likely to be excluded than their white peers, and that exclusion has been cited as a cause for the overrepresentation of Black youth in street crime. Like many kids who were dealt the cards that he was, Digga slipped into a life suffused with violence and run-ins with the police.

“The people who know me would say I’m kind, good-hearted. But the rest of the world is telling me I’m bad... Sometimes I don’t know how to feel”

He also started realising that he was good at music, and that he had a lot to talk about. Digga was developing his rap voice amid a decade of government austerity that entrenched high levels of poverty, cut £30bn in welfare payments, housing subsidies and social services, and decimated one third of youth clubs, leaving many kids like him adrift in the streets with few social supports to keep them on track. And so the stories he told, made up at first and then perhaps observed, were a reflection of entropy initiated not by drill music, but by government policy and inaction. He borrowed haunting, ominous piano beats from a nihilistic genre of music that originated in Chicago’s South Side, where kids like Chief Keef adapted trap music to convey their disaffection with and alienation from the inner city. And he told brutal stories on top of them. It’s only through music, and Harrow Club, that he was able to lift himself out of a hostile and claustrophobic environment.

On the subject of London’s youth club crisis, Digga is especially passionate. “It’s upsetting, because without Harrow Club I wouldn’t be who I am,” he says. “And if it ever closed... I mean, you never know what kind of chances they’re taking away from these kids. Back then, people wouldn’t have looked at me at Harrow Club and thought, ‘Rhys, this little kid here, he’s gonna go number one, he’s gonna be successful, he’ll have all these followers, he’s gonna make so much money’. Nobody would have believed that about me back then, because I was a troublemaker. So for the kids who are there now, I don’t know. It’s really hard to find the words. You know what I’m saying?”

I ask him what his proudest moment yet is, predicting that he might cite his community giveback to Harrow Club in 2021, when he bought and distributed piles of clothes and shoes to local youth, or the moment in 2017 that his “Next Up?” freestyle went viral, and he started making more money than he’d ever seen. Instead, he says it was the 2020 release of Defending Digga D, an intimate, Bafta-winning documentary that examines the legal tangle around his music and his struggle to turn a new leaf after spending 15 months in prison. In the film he comes off as charismatic and determined, and doesn’t shy away from accepting responsibility for his past mistakes. But there are damning scenes that reveal the ways that his efforts are stymied, as when he is threatened with a recall to prison for attending a Black Lives Matter rally.

“The documentary finally showed a side of me that is real life,” he said. “With celebrities, or anyone in the public eye, people see social media, they read headlines and, in the back of their minds they add all of these little things together and they make a character about you. But it’s in their heads. It’s not real. It might literally be the opposite of you. And I feel like I see that happening. I like proving people wrong.” Digga’s aspirations to work across mediums and disciplines are pushing the limits of what’s possible for a drill star. His desire to tell stories isn’t cordoned off by music. At the moment he’s acting in a couple of upcoming projects, and has been toying with the idea of writing his own TV show. “I have no idea what I would call it,” he says, “but it would be way more realistic and appealing to people like me than Top Boy.” He’s already proven himself to be a keen observer of street life. Now he wants to show all the ways that he can render it.

In 2020, British filmmaker Steve McQueen released an anthology series called Small Axe, a suite of five films that gracefully mapped various forms of brutality faced by London’s West Indian community from the late 60s into the early 80s. The opening film, Mangrove, took its name from a Caribbean restaurant in Notting Hill called the Mangrove, a common meeting place for Black intellectuals, artists and musicians back then. They played reggae music. People – Bob Marley, Nina Simone, Diana Ross, Jimi Hendrix – went to dance. They ate home-cooked food. The police raided it 12 times from January 1969 until the following summer; in one scene of the film, a constable accuses the restaurant owner of hosting gamblers, prostitutes and drug dealers. The protest that broke out in August 1970 resulted in the arrest of nine Black activists, who were charged with riot and affray. Their trial, which lasted 55 days, resulted in the first judicial acknowledgement of racism in the Metropolitan police force.

“When we talk about how Black music has been criminalised in the United Kingdom, we have to trace it to migration patterns from the Caribbean,” says Dr Lambros Fatsis. The story and fate of the Mangrove are not sealed into a vacuum. There was a time when fear of slave rebellion led to the banning of drums in British colonies. The beat is still dangerous. When the first soundsystems emerged in the 1960s with the birth of ska music – which eventually produced reggae – police began targeting and raiding Black clubs, centres and meeting places. “The logic that justified the targeting of reggae in the UK was primarily that it held a threatening political message, which was an anticolonial message of liberation,” says Fatsis. Rastafarians, in particular, were viewed as culturally threatening, and reggae came to be understood as a soundtrack to drug-dealing.

When grime music exploded in the early 2000s, a jagged mutation of UK garage and dance music, it arrived as a glitchy, street-level narration of government neglect. By 2005 the London Met had developed Form 696, a risk-assessment form that required nightclub promoters to give details about their events when applying for licences, including the genre of music they were playing and the ethnicity of its target audience. Venues hosting nights with R&B, bashment, garage and grime music often found their licences denied, or their parties shut down. “The police would sometimes have club owners hold the artists’ passports if they were performing, essentially treating them as suspects,” says Fatsis.

An alarming precedent has already been set. Internationally, many artists who make hip-hop music are quite literally treated as suspects. The last couple of years have seen several high-profile cases in which American rappers face criminal charges for things they’ve said in their music. Young Thug is in the midst of a 56-count grand jury indictment that lists YSL Records, the label he founded, as a gang, and their lyrics have been used to illustrate criminal conspiracy. Drakeo the Ruler spent three years fighting murder charges before he was found not guilty, after prosecutors used his lyrics to establish motive for a rap beef in 2016. Last year, dozens of top-billing artists, record labels and streaming services signed an open letter called “Art on Trial: Protect Black Art”, which addressed both the fundamental need for an outlet of free expression and the fact that rap music, like any other genre, is not inherently autobiographical. “No other fictionalised form, musical or otherwise, is treated this way in court,” write Erik Nielsen and David Dennis Jr, authors of 2019’s Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America. “That’s why we call this book Rap on Trial. It’s not art on trial. It’s not music on trial. It’s only rap.”

Form 696 was officially scrapped in 2017, but its aftermath is visible in the use of criminal behaviour orders to restrict the musical expression of drill artists. Dr Anthony Gunter, a youth worker-academic who studies and writes on youth violence, notes the irony in how the government is simultaneously announcing new rounds of spending cuts on social programmes while also clamping down on crime. “What I will say about Digga D, and others like him in drill, is that at least they have a way to express these events and these feelings. And yet, the authorities want to silence that,” says Gunter, who spent many years working in youth clubs. “Who would we be looking at if Digga D didn’t have this avenue? That’s what people are missing. Clearly, he’s an intelligent, articulate man who was able to create this space for himself to explore the feelings, dualities and challenges of his life. If he didn’t have that, what would we be looking at?”

“With celebrities, or anyone in the public eye, people see social media, they read headlines and, in the back of their minds they add all of these little things together and they make a character about you”

Perhaps because he was a ‘criminal’ before he became a fully-grown person, and because his whole system of morality was tried in court and in British media headlines while he was still a wayward teenager, Digga D’s sense of self appears to have been warped by what others have said and written about him, seen or not seen in him. He has become a surface for the fearful projections of people who have never met him. On this subject he is sometimes self-effacing, or prone to small displays of casual bravado. When I ask him about the distance between the image of Digga D in the public imagination and the real-life Rhys Herbert at home in private, for example, he says that people are entitled to their own opinions about him, and that he’s not really out to change anyone’s mind. “If you don’t want to look into who I am, then I don’t care what you think,” he says, dismissing the topic.

In the music is another answer. On much of his new music, Digga D is still gritty and fearless as ever, but he’s also sage and surprisingly vulnerable, attuned to his emotions with a newfound maturity that disqualifies his self-diagnosis as “not very good at talking about my emotions”. The new tracks are rife with humour, playfulness and machismo, but there are moments of stillness where his trademark confidence takes a back seat to self-doubt. Some lines burn with the intimacy of diary entries, as though the beat were a call for a therapy session. The pitched-down vocals on one new cut, for example, sound as if they’re coming from somewhere deep beneath the sea, and when the soulful piano melody wanders on to the track, Digga delivers his first lines calmly:

“God gave me life so I can’t tell him I’m suicidal / It’s been rewritten / But I still find time to read the Bible / I’m a rapper, that’s my title / Someone’s idol / So I’m mindful when I talk.”

A warm, chipmunked-up soul sample lends another track a sunny feel, but the second verse displays a self-reflexive lyrical clarity that breaks from the summery, feelgood atmosphere:

“Who knows if God still fucks with me / All of the fuckery, some of it troubles me / All of the things that I’m going through currently / I just need someone to show love and cuddle me.”

And in another track he plays me, there’s a preoccupation with the consequences of young kids looking up to him while he’s “preaching all this fuckery”, preceded by an observation that “when you’re the bad energy there’s no point burning sage”. It’s this constant push and pull between past and present, between images of a carefree childhood and scenes of a turbulent adolescence, that animate the tension at the root of this new music. These are dispatches from the psyche of a young man conflicted about his own goodness. He’s worried about, and fighting for, his own soul. It’s not a completely new theme, necessarily – for rap music, or for him. The schoolyard playground he evokes on “Stick in the Mud”, a standout from Noughty by Nature, is a setting where rounds of hide-and-seek end fatally, and where getting caught in a game of tag means the fun is really over. Even the mixtape’s cover depicts what the rapper calls “the evolution of badness”, a Darwinian progression from him fooling around with toys made of plastic to fooling around with weapons made of steel, from smoking weed and getting in trouble to picking up the mic and vying for a fresh start.

As for what he’d need to feel successful, Digga doesn’t hesitate to make a list: health, wealth, family, peace. He hangs on this final point, considers it. In spite of the success he has garnered, he feels nowhere close to finding peace. “I always think about my history, and whether it makes me a bad person,” he tells me later. “There’s this picture that the industry has painted of me, and it’s bad. But then the people who actually know me would say that I’m good-hearted, that I’m kind, that I’m innocent. And then everyone else in the world is telling me that I’m bad. And it’s like, what does that mean? Am I a good person? Am I a bad person? It’s confusing. Sometimes I don’t know how to feel. I don’t think I’m trying to answer the question, because I can’t answer a question I don’t have the answer to. I think I’m just asking myself who I am.”

Hair and make-up KARLA Q LEON at SAINT LUKE using TATCHA, grooming HB, model MARGAUX DOWLAND, set design JAMES HAMILTON, prop buyer HANNAH WHITE, model maker FELIX WENTWORTH, photographic assistants MICHAEL HANI, MESHACH FALCONER- ROBERTS, JED BARNES, styling assistants ROZ MOXON, NADIA DAHAN, make-up assistants CHERYL BASKO, CATHERINE MUNOZ, ANA TORRES ASPRILLA, production THEO HUE WILLIAMS, production assistants ALEXANDRA DELL’ANNO, KELLAND THOMAS-SMITH 213