With contributions from Sean Thor Conroe, Chris Kraus and Natasha Stagg, the New York magazine is publishing fast, ‘schizzed out’ short fiction – here, editor Patrick McGraw tells us more about the ideas that inspired it

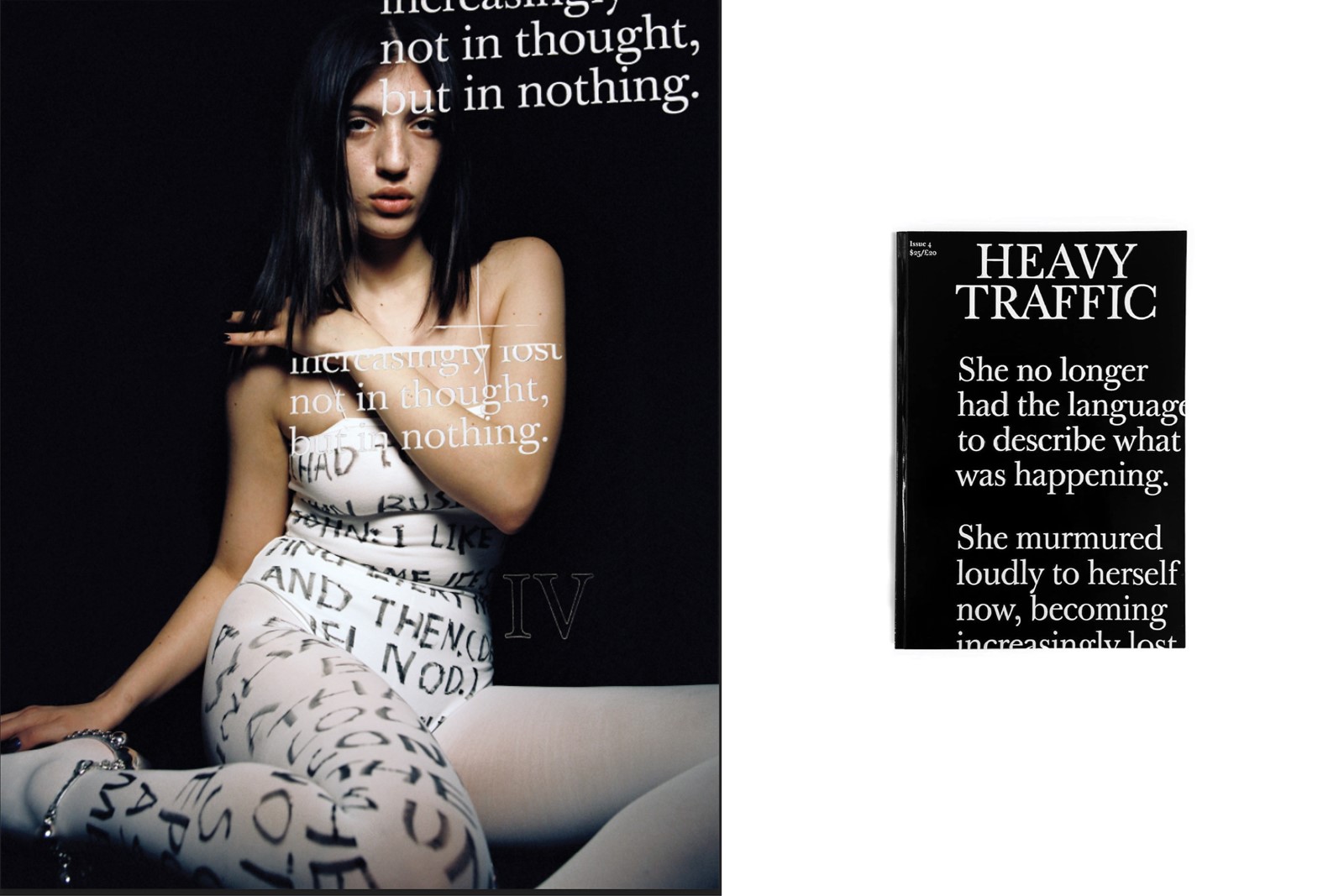

There are no images. Instead, the cover star of New York magazine Heavy Traffic is a barrage of text gleaming against a black void, the words chopped up and winding around its edges. “She no longer had the language to describe what was happening,” it reads. “She murmured loudly to herself now, becoming increasingly lost not in thought, but in nothing.”

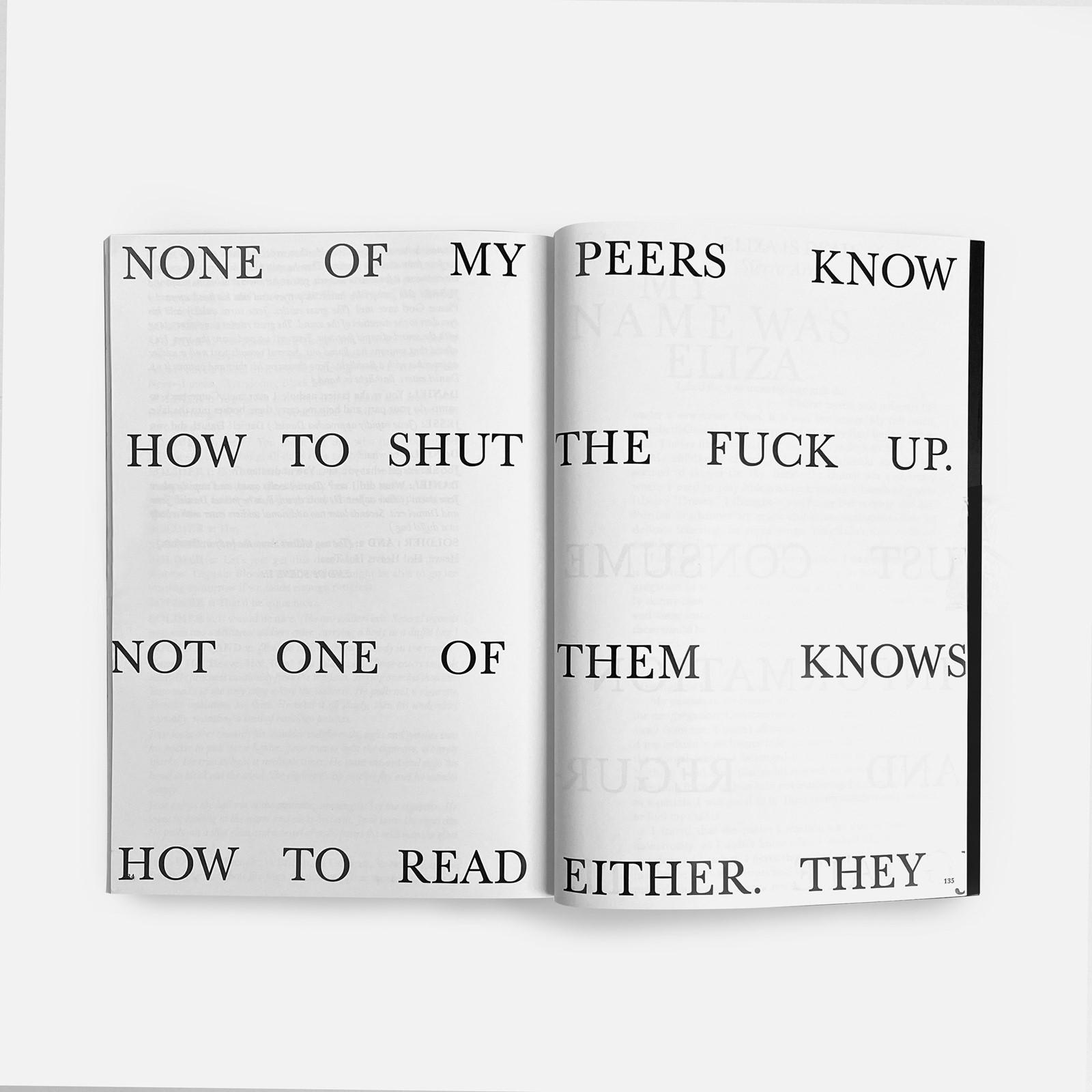

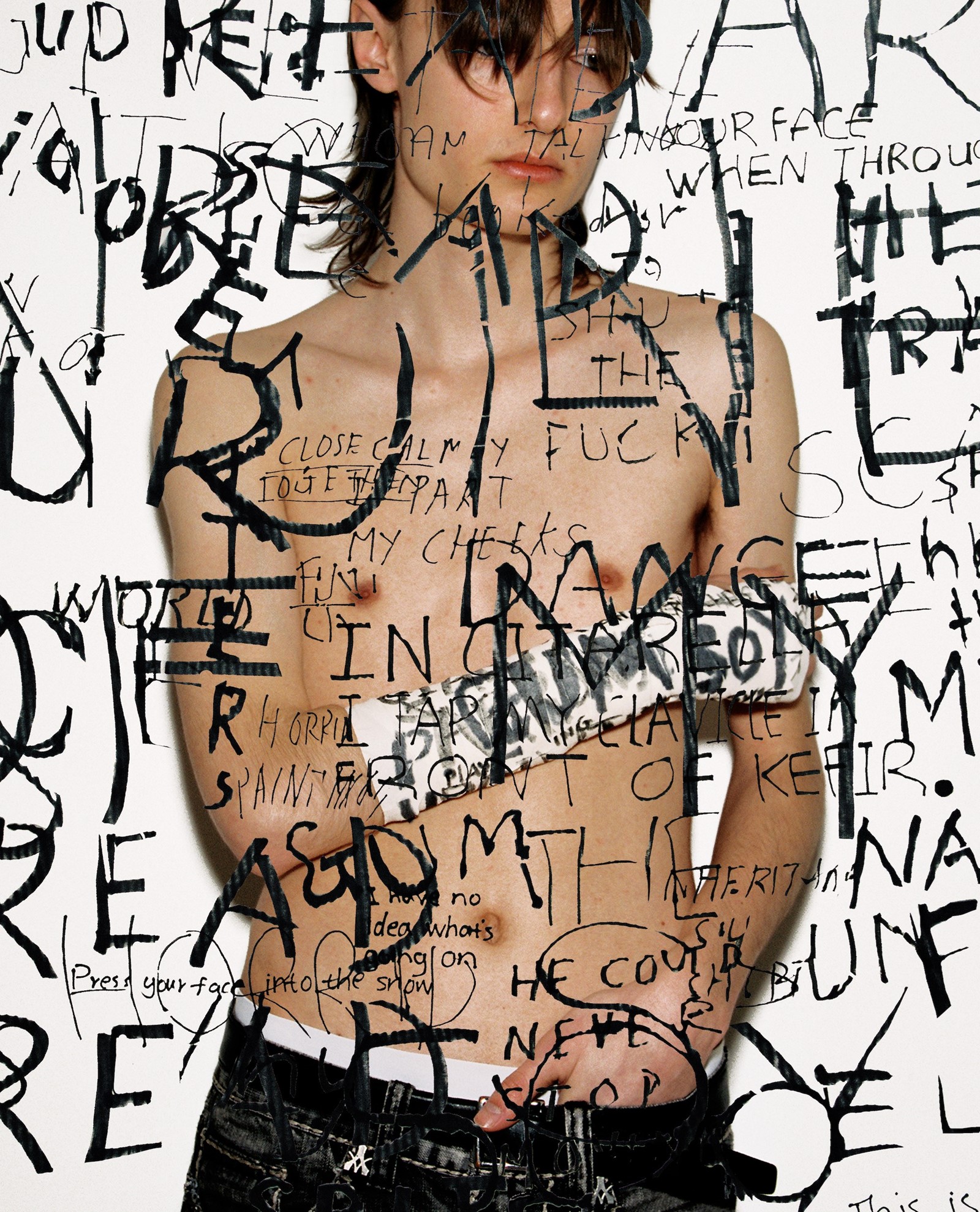

The literary magazine’s language, described by editor Patrick McGraw as “gibberish”, becomes increasingly haphazard and deranged as the pages turn (“Hard limit. Scarr-ed. sssh. whoAMiTALKingTO”). It almost feels like an IRL version of the infinite scroll, the words cascading through our brains like they do when flicking between feeds, tabs or messaging apps. We are a population that is becoming “increasingly illiterate”, McGraw writes in his editor’s letter. The new issue’s central occupation – not that the magazine officially has any themes – is to explore how language today has become detached from any meaning, beyond comprehension. “The more people see,” he writes, “the less they read.”

The fourth issue of Heavy Traffic, out now, boasts one of its most exciting line-ups yet. New York writers Natasha Stagg and Linda Yablonsky, journalist Kyle Chayka, and Fuccboi author Sean Thor Conroe have all contributed pieces of experimental short fiction, as have artists Jasper Baydala and Sedrick Chisom. In previous issues, there have been original pieces by Stephanie LeCava, Dean Kissick, Honor Levy, Lynne Tillman and Chris Kraus. “Half of the magazine is great writers,” McGraw tells me over the phone from New York. “But then the other half are usually artists, or even architects, people who’ve never published writing to any degree whatsoever.”

McGraw himself is a trained architect, who began working as a freelance journalist while studying, before making the switch full-time. But he quickly grew restless about the profession and its limitations (the writing itself, he says, felt “constrained“). Around the same time, in 2020, he started a group chat with writers Honor Levy and Marcus Mamourian, and they sent stories to each other to while away the long days of lockdown. “I just sensed there was a common thread through all of our writing,” he remembers. “It seemed like we had a shared goal, even if it was unclear what that goal was.” After a few months of back and forth, Heavy Traffic – a new space for instinctual, unbounded writing – was born, with Richard Turley (editorial and design director of Interview, and creator of anarchic NY broadsheet Civilisation) bringing the vision to life through unruly, text-heavy design.

Below, McGraw tells us more about the new issue, the threat of AI, the future of publishing, and where he thinks language is heading next.

Can you tell us about the Heavy Traffic approach to language?

Patrick McGraw: The term that we use is ‘schizzed out gibberish’. I think our collective relationship to language has changed dramatically – certainly in the last ten years, but especially in the past four or five years. AI is obviously a huge part of that: it seems to be taking over the role of traditional, structured writing, so people have actually gone in the opposite direction, and have become less able to comprehend language altogether. So much of the writing you see today – especially when you’re scrolling on Twitter, Instagram, or even looking at billboards – is just total gibberish. Part of that is the medium: when you scroll or flick through someone’s writing, you don’t really comprehend it, especially if there are images and videos. It turns into this huge blotch. So the language and design of Heavy Traffic is meant to represent that.

That said, I also think that language has become really important to people in another way, because we’re now, for the first time in a long time, turning away from the Enlightenment. We’re going back to superstitious, magical thinking. Part of that is because the only thing people have control over is their own narrative, or their persona and the curation of it, so the way they present themselves with language becomes very important.

Why do you think people are going back to magical thinking? And how do you think language plays a role in that?

Patrick McGraw: Language is representative of that. It became intensely structured over the past century, more structured than it ever was. Now, that kind of base, written language is going to be done by AI – and as long as humans don’t have that responsibility anymore, they will turn away from it. So I think you can augur this change through the way people are writing. To bring that back to the magazine, if you showed, for example, Cara Schacter’s piece to someone a couple of decades ago, I don’t think they would know what she was talking about. It’s just a complete slew of language, it wouldn’t be comprehensible.

The magazine seems to play a lot with the idea of how we consume and regurgitate information, and it does seem like originality is more elusive now. It feels so hard to write anything genuinely different or interesting, as if all this exposure to digital media is making us develop this kind of fuzzy hive mind.

Patrick McGraw: It seems like that’s by design. This world that we see is generated based on data of what it thinks we want to see, based on what we’ve already seen. I think that’s part of the problem with living our entire lives on platforms. You’re constantly only seeing versions of your past interests or past selves. It’s very hard to escape from this. When I read a piece of writing that I like, almost inevitably I get a sense of humanity within it that’s almost a reaction against the very rigid iron cage that is the world we’re living in, where you’re just constantly being fed things that you’ve already seen, already know, and are already supposed to like. There’s something inside of people that is reacting against this. You know there’s something wrong with this world. It’s so funny like, even around New Year, when people are doing like their year recaps – they’re already feeling nostalgia over something that happened just a few months ago.

It creates a kind of schizophrenia in people, right? Because you perform every day for this data, but that performance is still at odds with ostensible reality, even though it’s increasingly beginning to bleed into it.

“You’re just constantly being fed things that you’ve already seen, already know, and are already supposed to like. There’s something inside of people that is reacting against this” – Patrick McGraw

So do you think AI could end up being quite a liberating force for creativity? Or are you more sceptical about it?

Patrick McGraw: I just think it’s so funny, the idea that you can try to recreate something as multifarious and fallible as consciousness, which is actually multiple consciousnesses fighting for temporary dominance in your mind... a major facet of humanity is that it is fallible and erroneous. You learn from making mistakes and going into the areas you’re not supposed to. AI is the opposite of that, it’s trained to do things correctly from this concept of a single consciousness.

So how would you characterise the fiction in Heavy Traffic? What are the qualities you’re drawn to?

Patrick McGraw: It’s always very quick. I remember when I first met with Richard [Turley], the one thing that we talked about was the quickness of the writing. A good Heavy Traffic piece is one tone, very straight. I think that’s where Richard got the idea for the ‘cold open’ front cover: it starts very quickly, like a straight shot. But most of the pieces are able to give a sense of the current condition. When I was working in magazines, I always had this idea that you could describe the current condition by quantifying it, or by using data or information; I thought if I could organise an article or thinkpiece properly, I could somehow crack the code of what it feels like to live today. I’ve turned away from that, and I think most people have. Any attempt at quantification is only a different form of narrative creation anyway.

We’re speaking shortly after Vice announced its website closure. I want to know your thoughts on digital media at the moment, do you think there’s any hope for it? What’s your assessment?

Patrick McGraw: It’s going through a rough moment right now. I think digital media staked its claim on this platformisation of the world. But good media always creates its own almost separate world, and that’s why a printed magazine is so much more important than a website. It offers a level of immersion that people are craving at this moment. And as everybody becomes a ‘content creator’ themselves, the idea of going somewhere to get content becomes an antiquated idea, even though they are inevitably just making their content on platforms anyway.

At the same time, I do have a love for it. I was even just thinking this morning of how much I miss interviewing people, and actually how doing these kinds of articles and that form of content creation is very special and gives you a worldview that I don't think you can get anywhere else. Even though I’m saying these things are dying or antiquated, that doesn’t mean I’m happy about that being the case.

What about Substacks?

Patrick McGraw: It’s just such a horrible, horrible way to finance writing. It’s the epitome of us recreating an aspect of the analogue world in a worse way – so, instead of paying eight bucks to get a magazine with ten writers, you’re paying $15 to get three writers? I wish there was a better way. But I mean, you want to talk about an antiquated business model, making a print magazine is ridiculous; the amount of money we’re spending to produce this physical object, I’m not sure you can justify it in any sane way. But if Substack is the future, I don’t look forward to that future.

So what are you thinking for the future of Heavy Traffic? Are you thinking about that actively, or are you just taking it as it comes?

Patrick McGraw: I’ll certainly continue to match disparate writers from different worlds and mediums, and try to get them to write similarly. I used to tell myself that getting these bigger names was just a means to an end, and that in ten years time Heavy Traffic would be composed completely of people no one had ever heard of. The most exciting thing is when I get a random submission and it’s really good – someone I’ve never heard of, with no social media, from Kentucky or something, who is completely outside of any other scene that we know. That’s the most exciting thing in the world, and every issue has at least one or two people like that. Realistically, though, it’s very, very difficult to compose an entire magazine out of completely random people. All of that is to say, I do think a lot about where I want it to go in terms of tone and composition. But in terms of the trajectory of it as a business, I’m not quite certain. You just have to keep going.

Issue IV of Heavy Traffic is out now. Order a copy here.