In a head-to-head conversation, the two authors discuss the insidious nature of class in the UK, exploring how it affects taste, healthcare, the internet, and our radical imagination

In our new Class Ceiling series, we unpack how class actually affects young people today – from our jobs, to the way we have sex, to our general experience of the world.

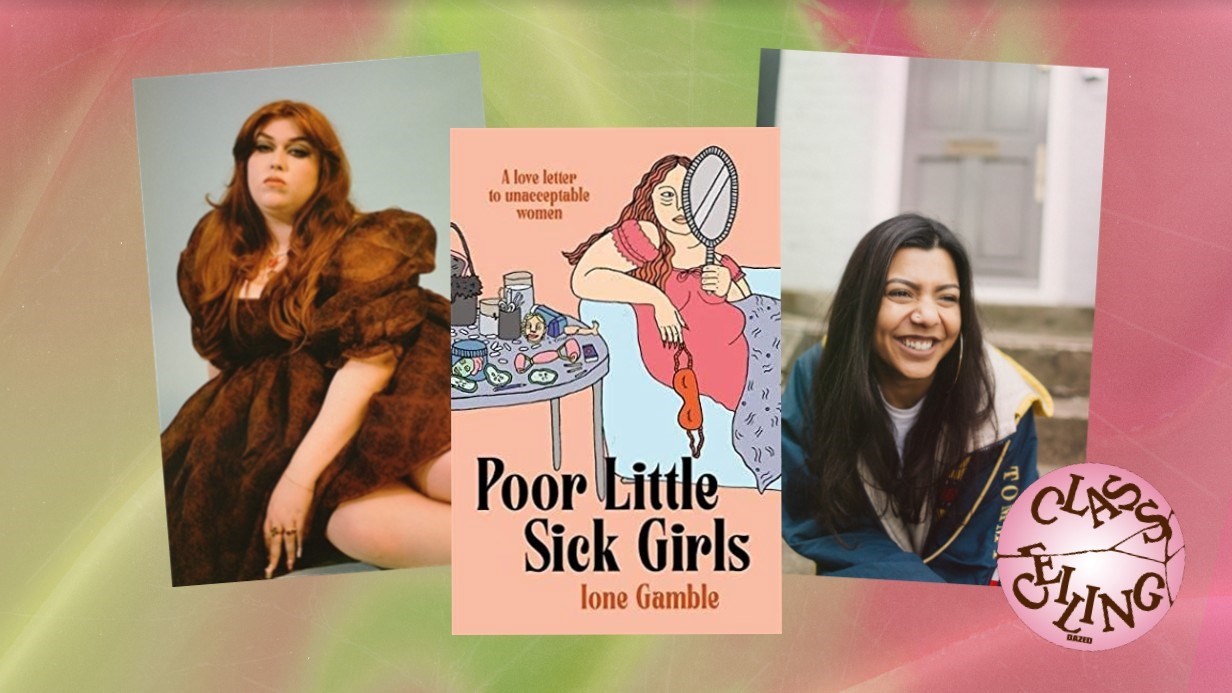

Ione Gamble and Kieran Yates are two authors who write from a distinctly working-class perspective, bringing a much-needed sense of warmth, humour and passion to conversations around things like body image and homeownership.

Inspired by the king of trash, John Waters, Gamble launched Polyester zine when she was 20 in response to a fashion and cultural landscape that continually revolved around one archetypal woman (see: thin, cis, wealthy) while shutting out anyone who deviated. Her debut book Poor Little Sick Girls, out on May 26, is an “anti-girlboss bible” of essays on feminism and pop culture through the lens of chronic illness.

By the age of 25, Yates had lived in 20 different houses across the UK, from London council estates to the Welsh countryside. Her debut book All The Houses I’ve Lived In, coming early next year, takes a personal exploration of Britain’s housing crisis, using each of her former homes to interrogate wider issues like gentrification, the shortage of social housing, the horrors of the unregulated rental economy, and their impact on people of colour in particular.

Here, Gamble and Yates get into it about all things to do with class, exploring its relationship to taste, healthcare, the internet, and more.

Kieran Yates: Ione, you have such a sophisticated idea of class, taste, and how those two things interact. I know your zine Polyester was inspired by the John Waters quote, “have faith in your own bad taste”...

Ione Gamble: Yeah. Growing up not having much money, you learn to put a lot of meaning into objects. Then suddenly you hit adulthood and it’s like no! You are a bad person if you have too much stuff. I found that really hard, that idea of “not liking” the right clothes or furniture, or loving things which are considered garish, like animal print.

The upper classes in this country rule everything. It’s not just politics, it’s also the magazines we read, the people designing our clothes, and the food we eat. They dictate the people who have good and bad taste. There’s this dominant belief that working-class people can’t make good decisions because they’re not making the right aesthetic decisions – if you can’t even decorate your home or dress yourself in a tasteful way, then why should you be trusted to make decisions about your own life, or about how our country is run?

Kieran Yates: Yeah. It’s the same with beauty. If you’re working class and you go to Turkey to get your teeth done, for example, you end up being demonised; people take the piss. It’s vain and it’s judged; it becomes this theatre of entertainment. But when this kind of work is done in upper-middle-class circles, it’s a version of self-care. It’s so far away from Audre Lorde’s reading of self-care as an act of radical warfare and self-preservation.

“If you’re working class and [get cosmetic work done], people take the piss. It’s vain and it’s judged; it becomes this theatre of entertainment. But [if you’re] upper-middle-class, it’s a version of self-care” – Kieran Yates

Ione Gamble: Self-care now just refers to using an expensive bath bomb or micro-needling. But if you actually look at the roots of self-care, it was initially for disabled people, then it was picked up by civil rights and feminist activists as a way of referring to community care. In the 70s and 80s, middle and upper-class people would always deem their wins as the stuff they have manifested by themselves; whereas working-class people always looked to community-based practice, and how they could lift up their surroundings. The way that we’re seeing wellness and health positioned now is definitely in that same middle-class mindset: if you have the money and the time to look after yourself, you’re alright. But then what about all the people who can’t do that?

Kieran Yates: Yeah – it’s the same with housing, health and education. In the 70s, there were housing activists who would adopt mortgage committees, where a trusted group within the community would donate money and then it would be distributed to help people get deposits. Now, all we have is this weird kind of announcement culture, where you’ll see an influencer or celebrity on Instagram holding up their keys in front of their new front door, as if housing is a luxury for the individual to pursue, or evidence of “hard work”.

Ione Gamble: Yeah. My hope comes from the internet, though – although it’s now full of fake news and bad infographics, it has the potential to be a tool with which we can share information very quickly and in an open-source way. It’s just so diluted now through capitalism and the pursuit of personal branding.

That said, I do also think the assumption that we should be speaking to everyone on the internet all the time has led us to the mess we’re in now. Now, every educational thing you do online assumes ignorance or idiocy from the reader, even on smaller community pages. We all interact with each other in such bad faith, because we all think everyone has absolutely no idea what we’re talking about.

“Society doesn’t value working-class people being able to make decisions about what actually fulfils us. It’s like, why are you buying a TV when you could be buying five bags of rice and two cauliflowers and feeding your family for 12 weeks?” – Ione Gamble

Kieran Yates: We also need to recognise how we are connected to our communities, and how the people on our street impact the world we live in. You can’t just opt out of the class experience. You can’t just put on a fascinator and go to the races and be like, “it's OK! I'm passing! I'm not oppressed by this system.” Of course you are! We all are. So when we talk about class, it can’t be over-intellectualised.

What about your books – can you tell us a little more about them and how they explore these issues?

Kieran Yates: My book, All The Houses I’ve Lived In, explores the precarity of building a home in a housing crisis. If you’re working-class, precarity follows you around. It’s up to us to find our own joy and beauty in that, and talk about community solutions for it. Millions of people in this country are being neglected; sometimes you just need to hear someone talk about their own experience to make things real for you.

Ione Gamble: My book is called Poor Little Sick Girls, and it’s a series of essays: some about class, fourth-wave feminism, and how my experience with illness has allowed me to be more cynical about our social movements and identity politics. Even the fact that we feel like we have to moralize our every purchase now – we can’t just buy shoes because it’s fun anymore. It’s the same with health and wellness, which is starting to feel more like religion. It‘s not good enough to just be fine, you have to be healthy. I wanted to challenge that.

I feel like there’s no room for joy anymore. That is another reason why working-class people are demonised so much, because society doesn’t value us being able to make decisions about what is fun or what actually fulfils us. It’s like, why are you buying a TV when you could be buying five bags of rice and two cauliflowers and feeding your family for 12 weeks? We don’t trust anyone to make the right decisions for themselves, or to do what makes them feel good.

“You can’t just opt out of the class experience. You can’t just put on a fascinator and go to the races and be like, “it's OK! I'm passing! I'm not oppressed by this system.” Of course you are! We all are” – Kieran Yates

Kieran Yates: Yes – we live in a society which is underpinned by excess and accumulation, but only for certain people. I remember in the 2019 election, I was canvassing in my local constituency in Battersea, and one of the main issues of contention was around the fact that Jeremy Corbyn had said that £80,000 pounds was enough for somebody to live on. People were furious at their front doors with me, saying “he doesn’t know what he’s talking about! There is absolutely no way that you can live on that!” The fact that you think you need to vote Tory so you can afford to send your kids to private school, even though it might put the rest of the country in dire straits, is fine. How is that attitude not demonised?

Ione Gamble: It’s the same with how doctors resent marginalised patients who advocate for themselves. They don’t take you seriously. There’s this underlying belief that, to be healthy, you should be at a retreat eating nothing and getting infused with vitamins that don’t actually do anything. If you aren’t, you must not care about yourself.

But actually, health is an ugly thing. It’s not fun to go to these appointments, get blood tests and have surgeries and procedures. So I think our response to that, online, is to try and make it beautiful through the lens of wealth. It’s all about going to a health retreat and sitting by a lake and wearing a white robe – but actually, that’s not what looking after yourself or anyone else is like. It’s like the dog work that no one else wants to do; it’s not cute. And I understand the desire to romanticize things that you might not consider to be fun, but capitalism wants to swoop in and make it a lifestyle.

Kieran Yates: Yeah. And also, it sells us this idea that, if you work for the NHS, you just have to endure life. It's just meant to be terrible. We have very little imagination about what our facilities could be.

“There’s this underlying belief that, to be healthy, you should be at a retreat eating nothing and getting infused with vitamins that don’t actually do anything. If you aren’t, you must not care about yourself” – Ione Gamble

Ione Gamble: Yes exactly. It’s like we’re constantly saying that the NHS has broken. The only out we're provided with is privatisation, but that money doesn't exist for so many people. There's a better way.

Kieran Yates: Yeah, I agree. I don’t think that the governance in this country – certainly in the last decade – has shown any radical imagination. But that’s why it’s important to listen to people who have done the organising; to experiment; to allow some room to make mistakes. Some of the discourse on the internet has made it very difficult to do that because it has made it difficult to be wrong – but we all know that that is how real change comes. And I think that there are practical things that we can do, and information we can share: it’s really important for your neighbour to know what to do if like immigration officers come to your door, for example, what to say to police if you see a stop and search, and to teach people what you know about money or class politics. We should feel empowered as a community to say shit as we see it, because the alternative is so much worse. Why should you have to feel like you have to submit to being constantly being oppressed? Nothing is worth that.

Ione Gamble’s Poor Little Sick Girls is out on May 26. Pre-order your copy here.

Kieran Yates’ All The Houses I’ve Lived In is out in early 2023.