With their soap-throwing theatrics at the National Gallery in October, two campaigners from Just Stop Oil showed how to wake people up to the climate crisis. Here, a range of vital activists from Mikaela Loach to Vanessa Nakate add their voices

Taken from the spring 2023 issue of Dazed. You can buy a copy of our latest issue here.

The future belongs to the young. And while we are all already feeling the effects of the climate crisis, it is those who have the most life left to live who will experience its harshest consequences. That’s why it’s the world’s youngest citizens who are fighting the crisis most ardently. They simply have no other choice. As 26-year-old activist Vanessa Nakate puts it: “Our future is scary. We have to do something about it.”

The Ugandan campaigner was first inspired to take action by Greta Thunberg, the now 20-year-old Swedish activist whose fierce determination to make world leaders listen up has paved the way for a new school of young climate advocates. But there is no one way to get into activism, as these multifaceted, idiosyncratic protesters show. Mikaela Loach, a 25-year-old Jamaican-British medical student, worked on migrant rights before the concept of climate justice drew her towards environmental efforts. For 18-year-old Autumn Peltier, it was witnessing local injustices that made her a campaigner for the water rights of Indigenous Canadian peoples. For others, such as 16-year-old Californian Genesis Butler, the change came early, and hit personally: she was just six when she became a vegan, and now helps other young people adapt their lifestyles for the good of the planet.

And there is more than one method of effective action. These advocates talk to world leaders, hand out leaflets, influence their peers on social media and organise strikes. Some even risk their own freedom, such as our cover stars, the brave young activists of Just Stop Oil. The controversial UK group has become notorious for blocking roads, spraying paint and glueing themselves to objects, all while demanding the government listens to their climate pleas.

For all these courageous young people, climate action is about seizing back their future from the governments, fossil fuel companies and oppressors who have stolen it from them – and from all of us. The question is: will you join them?

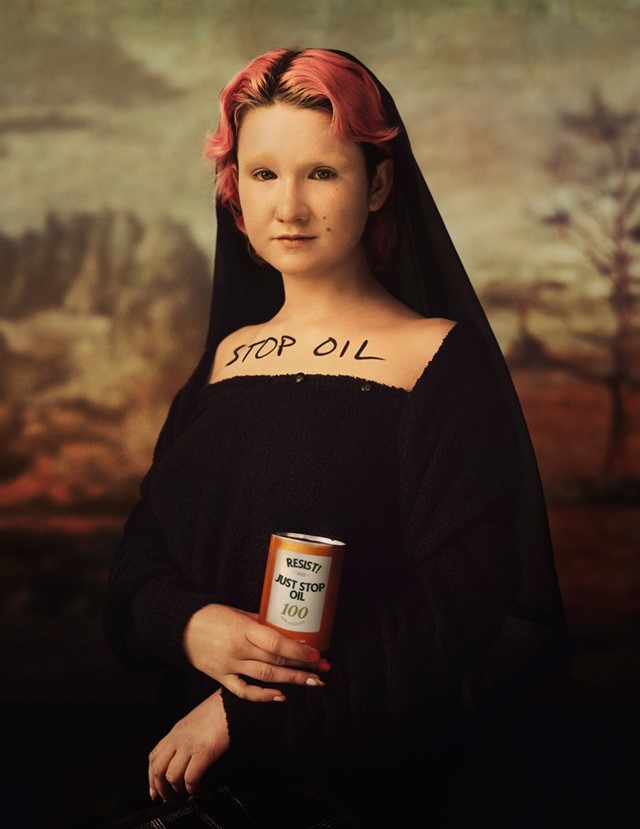

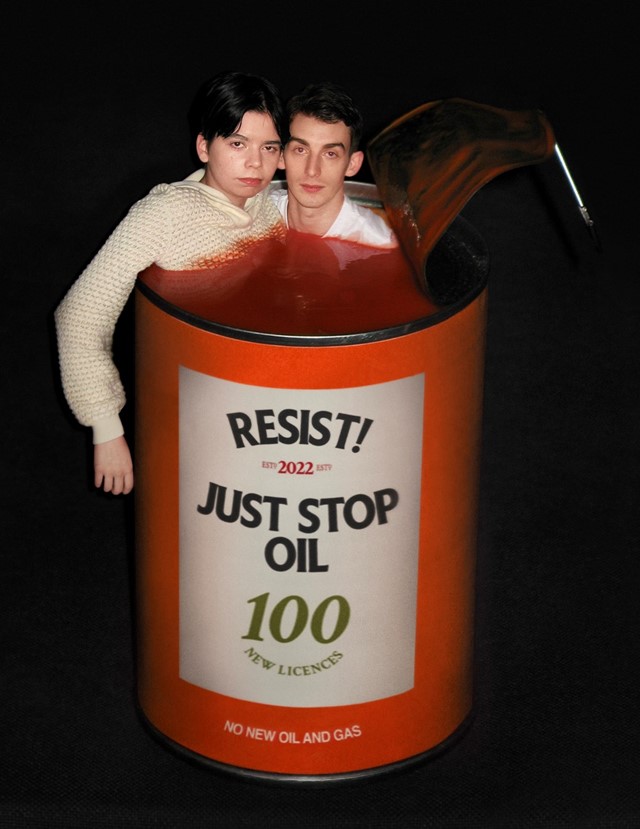

JUST STOP OIL

In the National Gallery on a Friday morning in October, Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland are flummoxed. They want to get close to Vincent Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” painting, but a group of children on a school trip are in the way. All Plummer can think is: “We can’t throw soup on children! They’re going to have to move!”

The pair mill around, trying desperately to get their bodies to remember what normal, non-suspicious behaviour in an art gallery looks like. Growing more and more anxious, they wonder how long they can bear to wait.

You know what happens next. When the kids are finally out of the way, Plummer and Holland take off their jackets, revealing Just Stop Oil (JSO) t-shirts. They approach the “Sunflowers”, open cans of Heinz cream of tomato soup and drench the painting. They kneel and glue themselves to the wall, then Plummer asks, “What’s worth more: art or life? Is it worth more than food? More than justice? Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting or the protection of our planet and people?”

It is a typically absurdist stunt from the climate coalition group. Plummer and Holland will throw soup at a £76m painting, but definitely not at the kids who happen to block their way. They will cover a painting in soup, then their hands in glue, a substance whose stickiness feels intrinsically silly, even childlike. They will – some would say radically, certainly cheekily – subvert the idea of value, and in doing so, draw the public’s attention to the government’s mishandling of the climate crisis.

‘We’re not going to be intimidated by prison sentences when there’s so much more at stake’ – Phoebe Plummer

Because above all, JSO want you to know the facts. In the summer of 2022, floods in Pakistan displaced more than 7.9 million people. Iraqi farmers are dying by suicide after drought led to crop failure for three years in a row. During two weeks when temperatures topped 40C for the first time in the UK last July, there were 2,227 excess deaths.

JSO believe they have the solutions. They are calling on the government to commit to ending all new fossil fuel development in the UK. The five years’ worth of oil the country has in storage will give us more than enough time to make the transition to renewables, which are now up to nine times cheaper than gas. Meanwhile, the Conservative government plans to issue at least 100 new oil and gas licences and has given the go-ahead for the country’s first coal mine in 30 years.

Plummer and Holland, both 21-year-old students, have been charged with criminal damage over their soup stunt, and are awaiting trial. “For every bit of nervousness I had in my body, I had twice as much excitement,” Holland recalls of the day of the action. They are the quieter, less energetic of the two, but in remembering that buzz they shake their head, grinning. Even via a shaky Zoom connection, I can see their eyes light up. It was only after they were released from custody that they learned a video of the souping had millions of views online.

“Seeing the impact it had,” says Plummer, “that felt more crazy than actually throwing the soup.” But not everyone was paying attention to JSO’s message. A Daily Mail article detailing their court appearance made no mention of their demands, “but it described what we wore to court. They’re more concerned about the colour of my skirt than our crops failing, than families losing their homes, than the 20 people who died in an extreme weather event in California. And when the most interesting thing they have to write is about the colour of a 21-year-old’s skirt – what aren’t they telling you?”

Plummer speaks with the learned tact of a longtime political orator. Even on a Monday night Zoom call with their three fellow JSO activists and me, they use dramatic pauses and rhetorical questions in carefully paced addresses. They have recently been released on remand after 28 days in prison for climbing a gantry on the M25 in November, and still have three crown court cases against them. But that isn’t stopping them. “We’re not going to be intimidated by prison sentences when there’s so much more at stake,” Plummer says stirringly, as if they were addressing a rally of thousands. “When the only future I see for myself is one of mass famine, severe droughts, flooding, wildfires and societal collapse, time spent in prison is irrelevant. But that doesn’t mean it was a nice place to be or an easy decision to make. I’m furious that I’ve been forced into this position.”

Since April 2022, when the group began its blockade of ten oil facilities across the UK, Just Stop Oil has become notorious. Alex De Koning, a 24-year-old science PhD student in Newcastle, occupied an oil pipeline in May last year. He remained in the “filthy” pipe, 15 metres above the ground, for 40 hours before he was arrested. Even today, he’s unsure how he found the nerve to do it, how he slept up there, so close to the drop. “But in a weird way, I knew it needed to be done,” he says, his mind focused on just one thing: getting the government to wake up to the crisis.

Emma Brown, a 31-year-old librarian and artist, has also blocked oil infrastructure, as well as spraying paint at a luxury car dealership in Mayfair, London, and gluing herself to a painting at a Glasgow art gallery. “Civil disobedience is about not being obedient to a system that is killing us,” she says. She is the moral core of the group – the pragmatic, down-to-earth organiser who uses the “empowerment” she gains from direct action to reignite in others the urgency of their activism. Part of the way through our call Brown has to dash off, “to make soup for my community”. None of the others seems to notice the aptness of that particular dish.

‘I ran in front of a moving oil tanker, sat down for 14 hours and waited to get arrested’ – Alex De Koning

In less than a year, these activists’ lives have changed irreversibly. They are regularly called “cultists” or “eco-terrorists” in the tabloid press. But they never expected to be liked. “We’re not doing this because we want to, we don’t want to be blocking roads,” De Koning says, soberly. “It’s a horrible thing to do to anybody. It’s a horrible thing for us to do ourselves.” He had never even been to a protest before he attended his first JSO event. “And yet, two weeks after my first talk, I ran in front of a moving oil tanker, sat down for 14 hours and waited to get arrested.”

None of these four activists can tell me what makes them unusual compared to the average person who is scared about the climate crisis, or what gives them the courage – or perhaps recklessness – to do what they do. In fact, a recent survey found that two-thirds of UK adults support non-violent direct action to protect the climate. Yet for most of us, the idea of risking our liberty – even for a cause so great – is unimaginable.

It’s at this point in the conversation I realise that the quartet’s measured approach, where each person knows which questions to answer and interruptions are impressively minimal, is not simply because of their professionalism. “Sorry, we all just laughed there a bit because we all simultaneously put in our group chat that we wanted to answer this question,” says Holland. I have asked why they think relatively few people are willing to get involved with direct action, and I’m just glad they aren’t laughing at what they could have perceived as a stupid question. It occurs to me that the frequency with which Holland turns off their camera might be to hide group-chat induced giggles, not simply because of their professed wobbly internet connection.

“The decision to step into civil disobedience or direct action is a massive decision to make,” says Holland, holding it together to answer with characteristic thoughtfulness. “Our education system – and I don’t mean just school, but media, everything we absorb – instructs us that people who go to prison are bad people. For a lot of cases, because our judiciary system is so broken, that’s just not true. Putting your body and your freedom on the line for the sake of this fight takes not just massive bravery, but massive amounts of unlearning.”

Plummer, whom Holland describes as their best friend, doesn’t think anyone in JSO is “different” from the rest of us. “We’re ordinary people,” they say, emphatically. “If you’d told me a few months ago that I’d spend my university freshers’ term in prison, I’d have laughed in your face. I’m not a criminal. I’m also not some kind of activist superhero. I’m a normal student who has woken up to how serious the situation is.” They take a dramatic pause before building to an inspiring fever pitch: “If you’re not fully standing up against these systems, then you are complicit. I’m saying ‘not in my name’ – and everybody has that power within them.”

Public disruption is a centuries-old tactic, but JSO are working in a distinctly new, heavily politicised climate. The last few months – of train strikes, nurses’ strikes, postal strikes – have “helped break the myth that disruption is targeting the public”, Brown says. It’s the government they aim to provoke. “So often climate action is pitted against workers, but the only people who have benefitted from the current system is the 0.0001%. We’re on the side of the workers.”

What’s more, “I’m living proof that civil resistance works,” Plummer adds, in their trademark rallying cry. “Maybe that’s why I know that there’s hope in it, because I’m queer, non-binary, but born female. So the only reason I’m able to vote, I’m able to go to university, I’m hopefully someday able to marry the woman I love, is because of people that have taken part in civil resistance before me. History has shown us that this does work.”

JSO will stop their public disruption when the government makes “meaningful changes”, explains De Koning, who is keen to clarify the movement’s secondary demands: that the government insulates homes; subsidises public transport and taxes the big oil and gas polluters. He reminds me that renewables are nine times cheaper than gas, and I see the faces on my Zoom screen dissolve into giggles. “They’re telling me in our group chat that I’m using the same lines as usual,” De Koning says. “I know I’ve already said it, but that stat really blows people’s minds.”

“It’s fine,” offers Plummer, just about recovered from their laughter. “I talk about this so much I’ve started sleep-talking about it. I woke my friend up, one night, saying lines! ‘We’re an island, why aren’t we using tidal power?’ – that’s another Alex line. Have you said that one yet?”

“You can tell we’re all dangerous criminals with no sense of humour,” De Koning snarks.

MIKAELA LOACH

“I feel an immense amount of pressure to be the hope machine,” says Mikaela Loach. “That can feel exhausting, because I don’t see hope as a thing that someone can give to someone else. Hope is something we create when we take action.”

Loach first got into activism as a teenager, when she went to Calais to volunteer in the refugee camp then known as the ‘Jungle’. Soon she learned about climate justice. The concept considers the environmental crisis not as an equaliser but as ‘the great multiplier’, and would inform Loach’s activist future. Loach got involved with Extinction Rebellion, and in 2019 locked herself to a stage as part of a four-day roadblock protesting Westminster’s connection to fossil fuels. She has since taken the UK government to court over its subsidies to the oil and gas industry.

The climate crisis “makes existing inequalities greater because it multiplies the effects”, Loach explains. “It is going to displace more people around the world and make pre-existing violent border policies worse. But at the same time, climate justice says that if we tackle this crisis through the lens of justice, we have the opportunity to transform the world. The climate crisis arose from the same systems that are causing harm towards people: white supremacy, colonialism, capitalism. To truly tackle the climate crisis, we need to get to these roots.”

‘White environmentalism [commends] an academic type of knowledge. I think there’s so much genius in the community, especially in the Black community, which has been organising around an existential threat of white supremacy for generations’ – Mikaela Loach

Loach has written a book, It’s Not That Radical, on the subject. But the writer, who quotes eagerly from Audre Lorde and Rebecca Solnit, knows that jargon-fuelled tirades won’t help the masses: the climate movement needs ground-up campaigning. “White environmentalism,” she says, commends “an academic type of knowledge. I think there’s so much genius in the community, especially in the Black community, which has been organising around an existential threat of white supremacy for generations.”

In July, Loach will return to her medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, which she paused to focus on her activist work. She still plans to practise as a doctor: “Climate change is the biggest threat to global health,” she says.

With her youth and acumen, Loach is increasingly looked upon as a beacon of hope – that hope machine. Recently she spoke at an event for insurers. She knew lots of audience members were investors in fossil fuels. “I don’t want any of you to tell me that I’ve inspired you unless you have changed your behaviour,” she told them. “Because what is the point of inspiration, if it doesn’t inspire you to take action?”

AUTUMN PELTIER

As a child of a First Nations community, Autumn Peltier grew up knowing two important Indigenous teachings: that she comes from sacred water – in which she floated inside the womb – and that she has a responsibility to protect the natural world. “My people have high respect for the land and the water,” Peltier, now 18, explains. “We treat it as if it’s a human being.”

Peltier grew up in Wiikwemkoong First Nation on Ontario’s Manitoulin Island, which lies on the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth. She was just eight years old when she learned about ‘boil water advisories’ – directives issued to communities not to drink tap water – when she attended a water ceremony an hour away from her home. That evening she went online and learned that an old uranium mine had contaminated the water supply. It has now been 25 years since these families have been able to use tap water.

“As someone who understands the waters, understands the lands, understands the animals”, the realisation “did take a really big toll on me”, says Peltier. Now enrolled in an Indigenous studies programme at college, she is measured when describing the emotional toll of this injustice, but a frustration lurks beneath her cool demeanour. “Canada is considered a very rich country. Yet some First Nations communities don’t have drinkable water.”

‘My people have high respect for the land and the water. We treat it as if it’s a human being’ – Autumn Peltier

In 2019, Peltier was named chief water commissioner by the Anishinabek Nation, and she has spoken at the United Nations and the World Economic Forum. She holds her Indigenous identity close, wearing traditional First Nations dress for public appearances and remembering her great-aunt, fellow water advocate Josephine Mandamin, as a mentor. “Indigenous people are looked down on,” she says. “It’s important for me to encourage other Indigenous people to see someone wearing those things, for them to feel comfortable in their traditions, with who they are in their own skin.”

Peltier’s biggest goal is to aid collaboration between Indigenous peoples and government, so that those affected are truly included in decision-making. In 2016, aged 12, she confronted Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau about a pipeline expansion that would put water supplies at further risk. “I am very unhappy with the choices you’ve made,” she said, before bursting into tears.

Peltier is still calling on the Canadian government to provide clean water for all. If she could sit down with Trudeau today, what would she say? “I would have the same message,” she says, defiant, “because in seven years, nothing has changed.”

Ellen Peirson-Hagger is assistant culture editor at the New Statesman.

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today.