Taken from the autumn 2022 issue of Dazed. You can buy a copy of our latest issue here.

This is not a comeback tale; instead, it is nothing short of the revival of Kelela. A jubilee, of sorts, for a beloved artist who hasn’t been gone at all – she’s been listening. Since dipping ever so slightly beyond our reach, she has been setting the conditions under which she constructs her world and creates her art. This has been her way since the release of her first mixtape, CUT 4 ME, in 2013 up until her last release, Take Me Apart, in 2017 and the remix album that followed.

In 2019, Kelela created her own reading primer filled with articles, books, podcasts, videos and documentaries and started to send it out to her friends, family and business partners. She included resources like Reader on Misogynoir by Kandis Williams, The will to change by bell hooks and Algorithms of Oppression by Safiya Umoja Noble. She sent links to the Seeing White podcast and IGTV videos from Sonya Renee Taylor about Black labour called, Are you stealing from Black folks? and More on Stealing from Black People: Right Relationship Beyond Capitalism. She even included work from Black men like Heavy: an American Memoir by Kiese Laymon and Damon Young’s viral article “Straight Black Men Are the White People of Black People”, adding personal notes like “Only thing I would add is that cis gay Black men are also the white people of Black people, especially in the creative industries where they are often allowed into positions of power right after white women.”

Additionally, she included documentaries that tied these radical texts back to her genre and medium of choice, dance music, through recommendations like The Last Angel of History (1996), which features interviews from the late Octavia E Butler and Greg Tate. Reading through these letters took my love for Kelela as a person and artist to a deeper level of unconditional love and appreciation, because I know this fight.

It is why she is often the soundtrack to every Black queer function, especially here in Los Angeles. Her voice, synths and beat loops pulsate through rooms under the groove of DJs like Sevyn of Fluid Radio, Terrell Brooke from the Cuties Color Party, or Bae Bae at Hood Rave. Let’s not forget those seminal sex scenes in both of Issa Rae’s hit TV shows, Insecure and Rap Sh!t. Despite being one of the few prominent Black women in the electronic dance music industry, Kelela’s impact on the culture is undeniable and honoured by those who have delighted in walking through her packed live shows, where she commands her audiences to create a path for us Black, queer and femme folk to take up space at the front.

After spending a 90-degree Sunday together for the first time in LA, making a URL relationship IRL official, she asked me to conduct her first interview in three years. So, with that, we rolled up, ordered lunch and jumped on Zoom for another few hours – this time, to publicly talk about her return to music, and everything that comes with opening yourself back up to public consumption.

Kelela: This has really only been a break from social media. You know that’s all we’re talking about. Because I’ve definitely been living a life outside of the internet, but also fully on the internet! As many of my audience members have noted online, liking all kinds of shit!

Facts. One time, I had just returned home from being at an event with an open bar. I felt cute, and one of your cuts came on my playlist, so I decided to record myself on my Instagram stories dancing in the mirror under the blue light in my bathroom [for you]. In the morning, I read her reply: “So the bar went up!” I have no shame, and it’s always a sweet reminder that you are very much active in a way that works for you online.

K: I value social media as a form of communication, but I also don’t feel the need to be on it all the time. In terms of this hiatus, I actually wanted to read and study for part of that time. I wanted to give myself time to think about these things and talk about them with the people in my life. I didn’t have a lot to share in those moments. I think it was better for me to listen. I need to take some time to figure out how everything I was learning was operating for me to get clear on what I was internalising and what was actually fully outside of me.

“This feeling of expansiveness is what I’m trying to give my people, and that’s what is at the centre of all this for me” - Kelela

While conversations about racism tend to focus on systems of oppression and society at large, colourism is a familial issue. Colourism dictates who we love and how we love them. It takes an uncommon amount of courage to talk about colourism in any room because it’s not only white people who are colourists. Black people and people of colour have innovated on this very specific form of anti-Blackness as well. I’m eager to ask you how colourism impacts you as an artist and how you are seeing it play out specifically in the music industry?

K: Out of all the creative industries, I would say that music feels like one of the most democratised industries because of the power of the audi-ence. However, there are people in the industry who control what the audience is even able to engage with. Because colourism exists within those ‘power players’ and also within the minds of the audience, it makes it so that everyone is a little bit less interested in somebody who has darker skin. So it looks like me having to do more. Whether that’s doing the most with live shows and fashion [in addition to the music] in order to reach the same milestones that the light-skinned girls are really just able to breeze through. And it’s been that way since the beginning of my career. And because colourism and internalised misogynoir are also present, if I express those observations, I can be seen as just being bitter about my results as an artist. So at the end of the day, there’s a way that I have been forced to internalise those feelings by thinking, ‘Oh, I need to work harder. I need to do more.’

You cannot outwork colourism. You can’t outwork misogynoir. Misogynoir determines Black women’s worth long before we sit down at the negotiation table. As artists who carry historically marginalised identities, our strength is in building better communities and partnerships with each other. What was the response to those letters that featured direct asks, like, “How are you creating a more equitable environment for people of colour, especially Black people? How many Black people are in positions of power at the company besides yourself? What about dark-skinned femmes? Or gender non-conforming people and those with disabilities?”

K: [People] shared with me that they were initially really put off by the letters. And then they reread them. They had to keep rereading it to really digest what I was saying and get past their initial reactions. Everyone seemed to be responsive on paper. However, I’m no longer at IMG. I’m no longer with my business manager. And, through the letter, I have been able to be released from my [publishing] contract with Sony. It’s an act of self-care. It’s just something that makes me feel more healthy and in alignment with my values. Ultimately I’m working to be in alignment with myself. What that has looked like for me is speaking up to make sure I’m in partnership with Black people. Over the last three or four years, I have also been paying attention to the ways that Black people are gatekeepers. I don’t want to be what one of my friends and I call ‘the only ones’. The goal is to look around and see more of us, not less. While I was writing this music, I was listening to The will to change by bell hooks. A thread in a lot of my work right now is my experience with misogynoir. While all of this was happening, I had also hit a real hard wall with men. I needed some renewal. I don’t want a Black Liberation movement without as many Black people as possible. I care about these people in my life but I have just been so disappointed by so many men as friends, family members, in professional partnerships and as lovers. I’m saying I don’t care and just yelling and leaving it there. But I do care. When I go to the music to write, I find out what I’m actually feeling about something. Because I come to my music candidly, I would step back and it was apparent to me that I was expressing being completely over experiencing a sense of dissatisfaction. Even in the longing, there’s still something that’s not being reciprocated.

I love sending you memes from fans like me begging you to bless our speakers with some new beats and vocals. I must admit, one of the dopest parts about spending time with you is being in earshot of you singing to yourself. I hear your influence in a lot of the music I’ve been listening to. When it comes to current popular Black music, we are sonically living in the future that you’ve imagined for us.

K: It’s such a beautiful feeling. I’m just gonna sit in that. I know that you mean it, and I think that’s why it feels so good. It also resonates with me and the work that I know I put in, and how isolated I’ve always felt in this space as a Black femme artist in dance music. When I came into the space, it wasn’t giving the amount of variety that we have right now. I’m experiencing so much relief around that because there are so many Black artists who have filled in this space. It was not giving that six or even eight years ago. Now, it feels so very sweet receiving these words and also having the experience of listening to other people’s music and hearing the influence. It’s exciting. I also feel like this moment in music is the result of the 2020 [Black Lives Matter] uprisings. It feels like a lot of people letting go of their internalised homophobia and racism. You know, just letting go of a lot of bullshit we have been taught to believe about ourselves for decades. White people didn’t change much. But n***as! Black people! We’re doing the work of expanding. I witnessed my peers and myself actually allowing ourselves to get sick of the shit. Giving ourselves permission to feel more emboldened and more unruly and vehement. And that is where I think a lot of the power of the last few years lies. We’re in this moment where a lot of people are wanting to make dance music; there are people who feel inspired by it and people who are ready to receive and embrace it. I think that’s a result of us starting to reckon with the self. There are a lot of implications for historically marginalised artists with big-name artists wanting to make electronic dance music. My hope is that it leads to something concrete for dance music and the historically under-resourced artists who are and have been making dance music. I want more people to develop a sense of pride in the artform as a whole. For me, that’s a really important thing. Because Black dance music is a healing knowledge, you know?

When this article comes out, your new single will have just been released. How would you describe this song?

K: “Washed Away” is a heart check-in. I think it’s important to me to start with a real check-in, like, how’s everybody really doing? Rather than coming out the gate on a party tip!

“‘Washed Away’ is a heart check-in... It’s like a baptism, it makes me think about all that we’ve collectively been through. There’s hope in it” - Kelela

But it wouldn’t be a Kelela takeover without the party tip popping out too! We will be dancing and crying!

K: There are a lot of moments where I’m just improvising on the song. And I started thinking about why. Where is this coming from? Why am I saying, “Far away. Washed away”? And it just feels like a cleanse. It’s like a baptism for me, and it makes me think about all that we’ve collectively been through. That’s the feeling, and it gives me a sense of triumph having made it through. There’s hope in it. I was talking with my friend about what this music feels like. I want to send out a clear message to Black people, who are my core audience and who I intend this music for, that you n***as are worthy. This time away has shown me that I have been very slowly building my world [the whole time]. Which is funny, because I feel like the dominant music business framework says that, if you go away, people will forget you. For me, it feels like the opposite. Because the way that I’ve been consistently vulnerable in sharing my real self through my art has kept me present with my audience. Over this time period, it’s almost like the volume has turned up. The world that I’m building has been made apparent through these memes and tweets and other expressions online, where people are either making a joke or saying something really sincere about me and my work. The undercurrent to it all is that they remember, and it’s based on a value system that’s rooted in being part of a club where everybody wears their hearts on their sleeves. It’s very smart in a way that is specific to queerness. A type of queer commentary where you are seen even in the margins. It’s loaded with knowledge that holds a special kind of tenderness and holistic consideration. I can only know what I’ve built through these types of responses and feedback. I am being made aware of the type of world that I’m building because my audience is giving the thing back to me. It feels like it's coming from such an honest place and not a trendy one.

Your music and visuals are made possible through the radical imagination of Blackness. I’ve watched one of those clips you sent over to me, and it has a feeling of... how the hell did you do this? What strain of weed is this?!

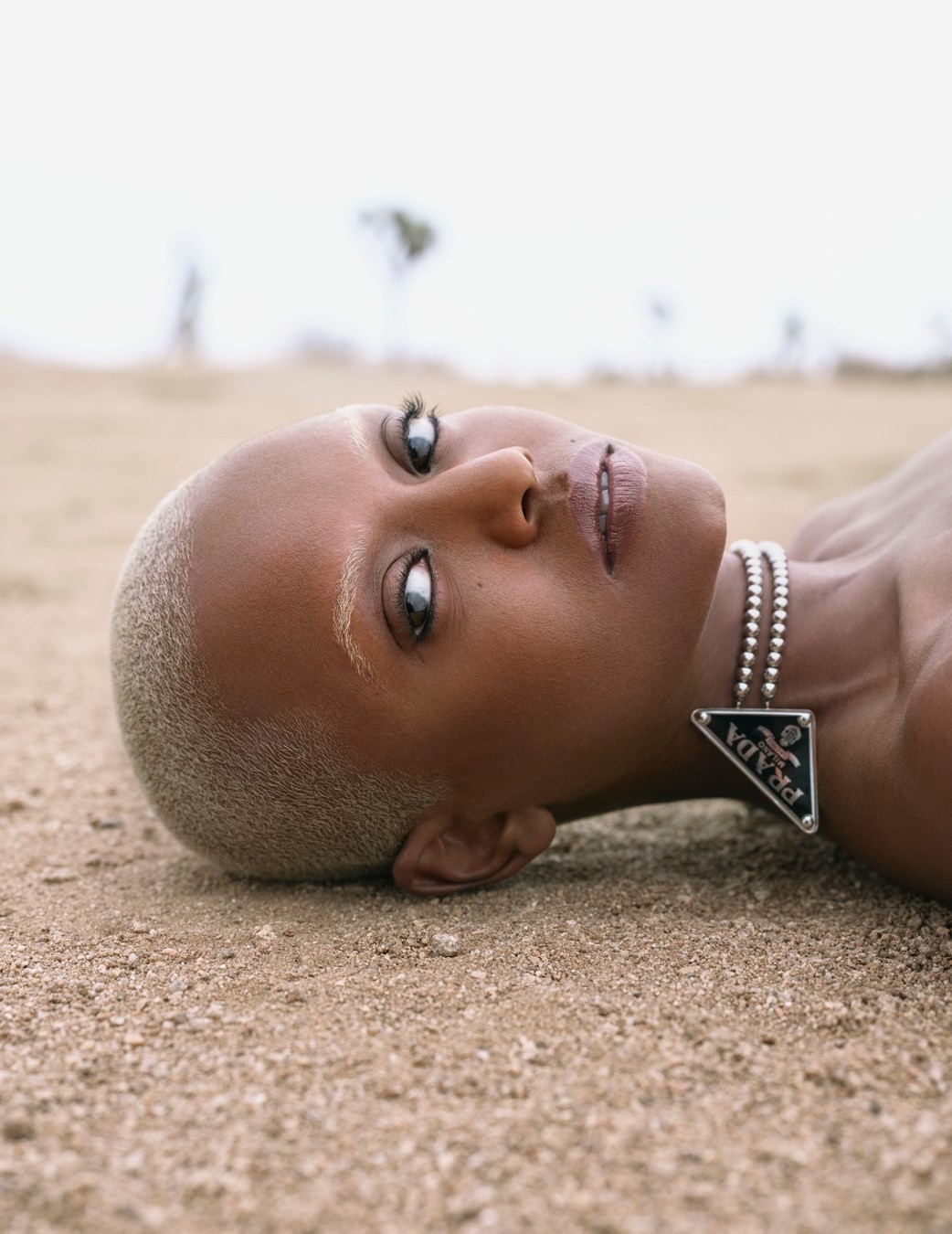

K: I’ll frame it like this – there are the aesthetics of Afrofuturism, and then there are the actual feelings, experiences and politics of Afrofuturism. We are building our relationship with visual and narrative signifiers through these images. For me, the end result is creating images that make Black people feel like we are actually this big! That we are worthy, and this is how large and expansive it can get. This feeling of expansiveness is what I’m trying to give my people, and that’s what is at the centre of all of this for me. I’ve never really named that framework in that way. But I think it’s an ethic I’ve been really striving for this whole time. I’m grateful to have been building this out over time, especially through the music I will be putting out. I like pairing the music with a visual language that produces a catharsis for Black fans specifically. It can work for all marginalised people if it works for us, but I’m really thinking about us.

I’m so excited for Kelela fans and the people who will get to experience your work for

the first time in an age of accessible social commentary and music history because of how lovers of music keep expanding their use of technologies like TikTok. We deserve to feel all of it. The anger, the dancing, the pleasure and the love that is housed in Black creative practices.

K: Yes! It’s time for us to dance. For everyone else, it’s not vibes right now. It’s clean-up time! The fact that they get to listen to some cute music should really be enough. But stand on the edge!

Beam us up, Kelela!

Hair MATT BENNS at CLM using ORIGINAL & MINERAL, make-up RAISA THOMAS at E.D.M.A using DIOR and YVES SAINT LAURENT, nails SOJIN OH at FUTURE REP, set design OLIVIA GILLES at JONES, photographic and lighting assistant BENJAMIN CALLOT, photographic assistant MANDO LOPEZ, make-up assistant EUNICE KRISTEN, production AMY GALLAGHER at WE FOLK, post-production STUDIO PRIVATE, casting MISCHA NOTCUTT at 11CASTING