For over a decade, Michael Joseph has documented the young Americans riding the rails as part of this largely overlooked subculture

In 2011, photographer Michael Joseph was in a taxi driving through Las Vegas when he saw a man standing on the side of the road with a sign which read, “ARIZONA OR SOUTH”. Something about his appearance caught Joseph’s attention. “He had striking features,” recalls the acclaimed American image-maker. “His hair was a faded blonde; his eyes, striking blue; his face, red and sunburned. He had an identifying anchor tattoo that swirled around his cheek.” Joseph asked the driver to stop and let him out. After taking his photo, they went their separate ways. “At the time, I didn’t think much of our interaction,” Joseph tells Dazed. “I didn’t write down his name or ask his story. This was a mistake that led me to search for years to come.”

Lost and Found: A Portrait of American Wanderlust (published by Kehrer) is, in essence, the manifestation of that search. Shot over the following decade and beyond, Joseph’s latest photo book is a collection of portraits of young travellers who, for many and various reasons, have opted out of or been denied access to mainstream American culture and are instead living nomadically on the open road and the rails.

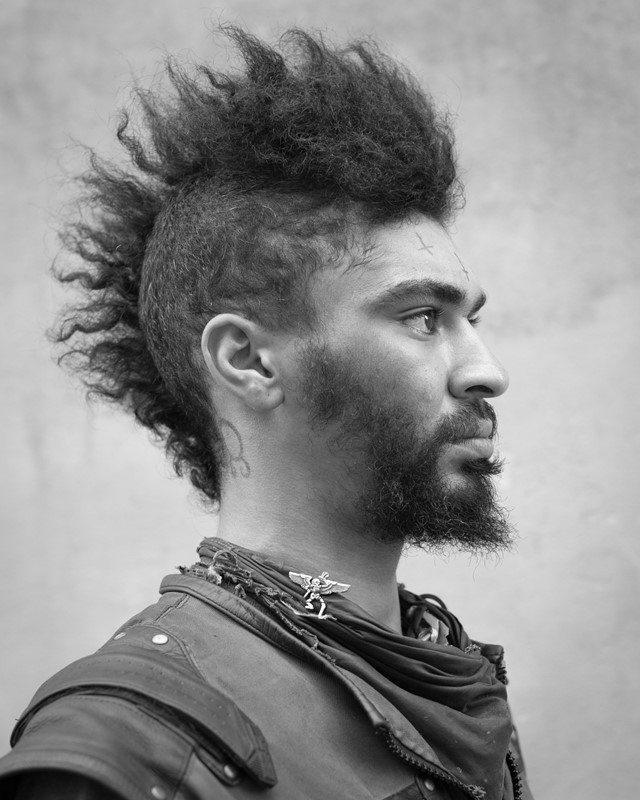

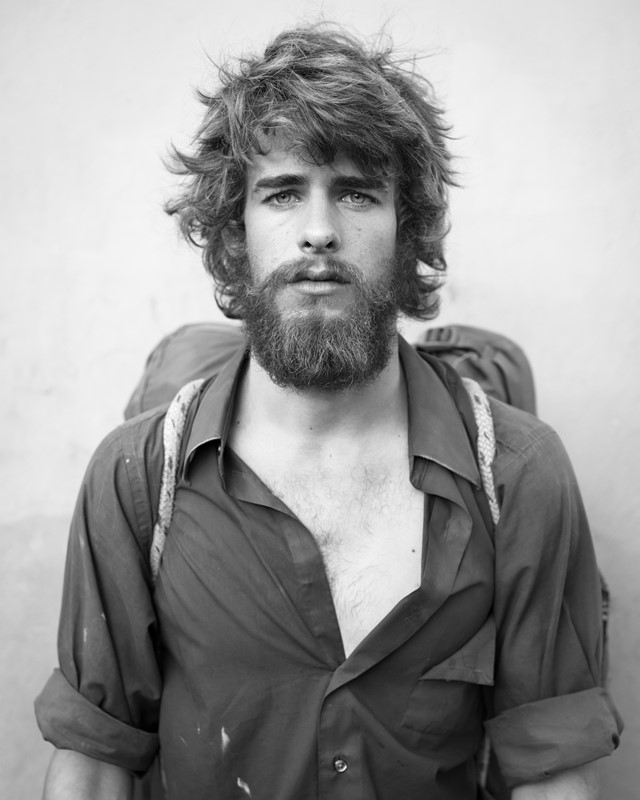

Leaning into this deeply American narrative – which recalls John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and Jack Kerouac’s On The Road – Joseph shot in time-honoured black and white. He explains, “I wanted the images to feel classic, timeless, and nod to the history of wanderlust in the United States.” Yet, while the portraits retain the dignity of their subjects, Joseph neither romanticises nor pities the hardship endured by this subculture. Instead, the portraits “remain raw, capturing bruises, cuts, dirt, and scars”. Alongside his captivating portraiture, Joseph includes individual voices in the form of stories or reflections in their own words; text which, together, offers a fragmented but insightful glimpse into the experiences of those he meets.

Joseph did eventually meet the man with the anchor on his cheek again. After a great deal of enquiry, he discovered his name was Knuckles and, three years after taking that original portrait in Vegas, the photographer was on the subway in Chicago when he spotted someone with the same distinctive face tattoo. “I was stunned. Was this possible?” Joseph marvels. “I approached him and asked if his name was Knuckles. I showed him the portrait we made together. It was him. He jumped up and gave me a hug.” After exchanging information and taking a picture together, they parted. But, as wondrous and improbable as it seems, they would cross paths again in strange and serendipitous ways on their mutual travels.

Over the years creating Lost and Found, Joseph became more enmeshed in the world of this subculture than he necessarily expected to, even, on one occasion, agreeing to hand deliver the ashes of a departed traveller from one state to another at the behest of the deceased’s mother. “As time passed, I would run into travellers multiple times in different locations. We kept in touch by phone, text, and social media messenger. Some passed away. Others settled off the road to be with their children or start their own families. Some continued to wander,” he tells us. “I intended to tell the story, but never to became part of it.”

Below, we speak to Michael Joseph about his time he spent among America’s young travelling community, how he composed such astonishing portraits, and what his project reveals about this faction of youth culture who reject the inherited ideals of the mainstream.

What’s the story behind this project and how it came to be? How did that initial interaction lead to Lost and Found?

Michael Joseph: At the time, I was working on a collection of street portraits of strangers. I wanted to meet people I might not otherwise get to meet day to day. I wanted to afford the viewer the same interaction by making close portraits. After I met my first travellers in Las Vegas, I began photographing them on streets all over the country. New Orleans, Austin, Cambridge, and New York City became the most productive places to make portraits. In the process, I learned that the man’s name was ‘Knuckles’ and that he was well-known among other travellers. Every time I went out to shoot, picking up clues about the subculture as I continued to document it, Knuckles was in the back of my mind.

“I excluded the background, leaving out city streets, train yards, squatting houses, underpasses, and passersby. I didn’t want to pin down any traveller to a specific location or place, as their place was everywhere” – Michael Joseph

How did you go about finding the young travellers and getting to know them and their stories?

Michael Joseph: At the beginning of the project, these portraits were made alongside other street portraits. But as I became aware of the traveller subculture and became closer with many of them, I decided to split off the project and make it its own. Soon I also started collecting audio and written stories. There were a handful of travellers who were very well known and would introduce me to others. By spending time with each traveller and then keeping in touch through text or social media messenger, I followed their lives as time progressed.

Soon, when visiting any city, I knew where they would be staying, and many contacted me as they would be travelling through my hometown of Boston. The most important part wasn’t necessarily making portraits but getting to know each traveller and their stories. By learning smaller individual stories, I was able to start to piece together a much bigger story describing the subculture. By staying in touch with many travellers I was able to see what happened to each as time passed and see what they learned over time being out on the road.

What were the guiding principles for you when shooting these portraits?

Michael Joseph: I wanted to photograph each traveller in a formal pose or composition to command importance, dignity, and respect. I excluded the background, leaving out city streets, train yards, squatting houses, underpasses, and passersby. I didn’t want to pin down any traveller to a specific location or place, as their place was everywhere. I wanted the portraits to be made close, often with direct eye contact so the viewer was forced to engage. I wanted the portraits to remain raw, capturing bruises, cuts, dirt, and scars. Travellers were not to be pitied nor romanticised by the viewer. I used my surroundings, such as walls and doorways, as backgrounds. I used natural light or even a streetlamp in a few cases after the sun had set. I photographed each traveller alone. I recorded their stories, some to be kept private and untold.

“If anything unites this subculture it is the search for freedom and a sense of wanderlust” – Michael Joseph

It seems to me that this is a particularly American story. Would you agree? And in what ways do you think this project comments on the American dream?

Michael Joseph: I do feel that this is very much an American story. Our country was developed by moving out to the West and has an ‘on the road’ history. The 1930s Dustbowl Era spawned the ‘hobo’ who were often children sent out on the road by their parents to look for work. With no money, these hobos rode by train as it was a free method of getting around. Jack Kerouac and his writing inspired the Beat Generation of the 50s. 1970s Haigh-Ashbury hippie culture rejected the status quo and held ideals of freedom. The 1990s East Village Punk Squatter of NYC also rejected societal norms. Each of these generations was a subculture that was often held together by certain music, art, and clothing. Each contributed to the culture of America.

Today’s traveller really does combine a lot of these characteristics. Look closely at their clothing and tattoos and you can see nods to the past while they create their own version by taking elements of the past and moving forward.

The American dream consists of the ideal that every citizen should have equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative. A more modern version of the dream incorporates fame and wealth with personal factors such as a secure retirement, financial independence, parenthood, and fulfilment through work.

In your own experience, what shared values and ideals do you feel motivate this group of people as a subculture?

Michael Joseph: Holding two jobs to make ends meet and being confined to office cubicles aren’t really the way people are meant to live. Instead, travellers reject a life that is expected for one of wanderlust and discovery. They are escaping a prescribed way of life that society has set out for them. If anything unites this subculture it is the search for freedom and a sense of wanderlust. ‘Ride free’ is often inscribed on patches or tattoos. There is a large sense of community and connection where people are driven to help one another, and intense personal bonds are formed. Perhaps these bonds – driven by survival and mentorship – are intensely rewarding compared to those that we are now living on a virtual platform. There is a greater connection to the land and outside elements that an everyday person is missing, confined to a small office cubicle or home for 40-plus hours per week.

The book reveals the feelings of a subset of youth that doesn’t fit in with a life that American society has prescribed for them. These travellers have wanderlust coursing through their veins and have escaped some aspect of life that leads them to the open road. In essence, the way they are wired doesn’t correspond with how society tells them they should live.

Michael Joseph’s Lost and Found: A Portrait of American Wanderlust [published by Kehrer] is available to order here now.