Director Pablo Berger talks about his Oscar-nominated new film, Robot Dreams – a ‘joyful and depressing’ tale of queer love in the big city

Don’t tell the director of Robot Dreams that his Oscar-nominated animated feature is a children’s movie. The mistake I make, over Zoom, a few days after the Oscars ceremony, is to compliment Pablo Berger on how his beloved sci-fi plays just as well for adults. “It’s the opposite,” the 60-year-old Spanish filmmaker cheerfully clarifies from his home in Madrid. “It’s an adult film that kids like. This is a cinephile film – it opened at Cannes! It’s a personal film that came from my gut, like in Alien.”

After a month doing screenings and events in LA, Berger is still on a high from his Oscars experience. Made for $5 million, Robot Dreams cost a fraction of its competitors in the Animated Feature category: Elemental and Into the Spider-Verse had respective budgets of $200 million and $150 million; The Boy and the Heron, the eventual winner, is reportedly Japan’s most expensive film of all time. “Every time somebody gets onstage at the Oscars and says they didn’t prepare a speech, it’s a lie,” says Berger, who knew the odds were against him. “I had my speech ready.”

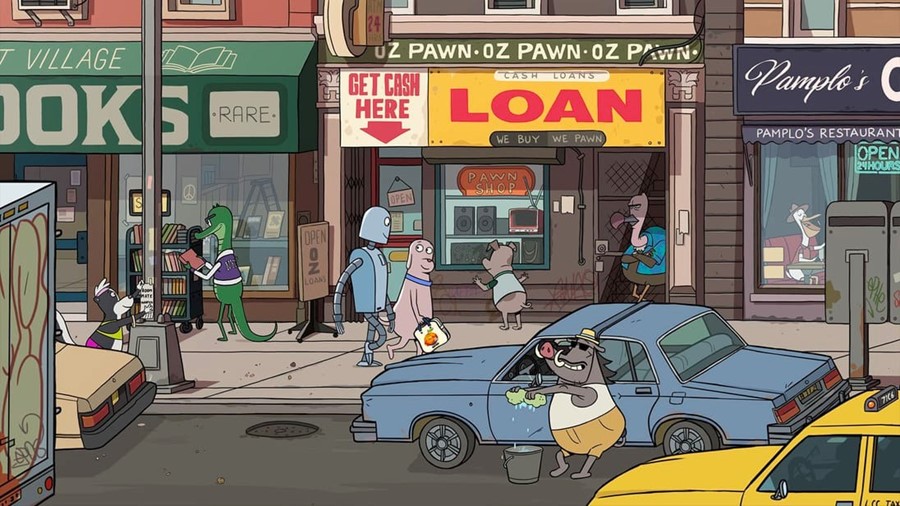

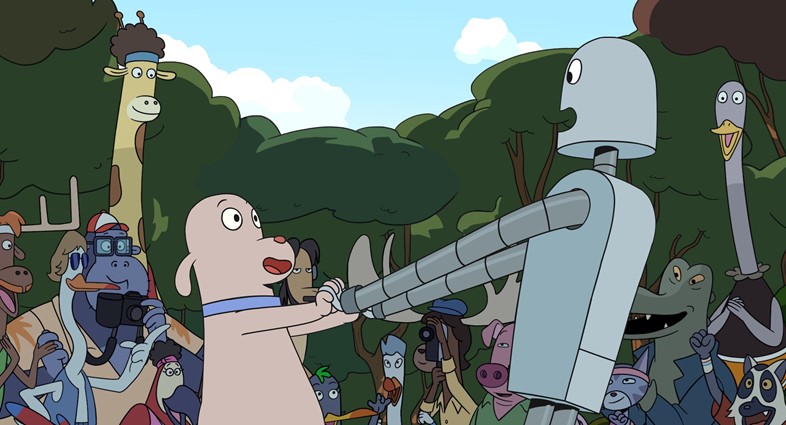

Both joyful and depressing, Robot Dreams is a hand-drawn, wordless fantasy set in a version of 1980s New York where anthropomorphic animals roam the streets. While the absence of humans makes it sound like a utopia, the creatures still suffer from existential despair. Alone at home, a dog (let’s call it Dog) spots an advertisement for a mechanical companion (let’s call it Robot), and orders one through the post, rather like a cross between IKEA and Spike Jonze’s Her. Soon, they’re cavorting to Earth, Wind & Fire, paddling on boats, and holding hands. “Most kids are going to interpret it as friends,” says Berger. “But I think most adults see them as lovers.”

Regardless of whether they’re romantic or platonic, Dog and Robot’s partnership is cruelly ripped to shreds. After frolicking at the beach, Robot lays dormant on the sand, rusty from the water, too heavy for Dog to carry home. The next day, the beach is barricaded, leading Dog and Robot to separately fantasise about a reunion while confronting their total, utter loneliness. Most of the film, really, is about two characters failing to move on: one is a canine floundering with new relationships, the other is a machine slowly fading through neglect. Pixar, this is not – unless Up was just the opening 10-minute stretch about death.

As in Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel of the same name, Robot Dreams doesn’t indicate whether Dog and Robot have a gender. Subsequently, the ambiguity, plus the lack of dialogue, has led to online speculation that the film depicts a gay romance. “If you look at Letterboxd, there are so many queer readings of Robot Dreams,” says Berger. “I’m so happy when people see queer elements in it. You can interpret it as male, female, non-binary – it doesn’t matter. Emotions are universal. Now, gender has become one of the main trending topics, but we started five years ago – maybe we were ahead of time. I’m really happy we went with genderless characters.”

Before Robot Dreams, Berger directed three features, all live-action, bizarre, and not exactly child-friendly. Torremolinos 73 follows a Bergman wannabe who shoots porn, while Abracadabra is a violent, raunchy comedy about a wife whose husband is possessed by a serial killer. Prior to Robot Dreams, he was best known for Blancanieves, a monochrome, wordless retelling of Snow White amidst the sport of bullfighting. Still, the director insists that his transition to animation felt natural.

“Instead of using a camera, I use hundreds of artists doing hand drawings,” Berger says. “It’s basically the same. I’m not a cameraman and I’m not an art director, but I know what I want, and I know how to communicate it.” He explains that, in live-action, he instructs the performers to not overact, and to instead communicate through their eyes. “With the animators, I look at the eyes of Robot and Dog. If their eyes don’t tell me the truth, I keep working on it. Honestly, I talk the same way to actors and animators. I tell them to trust the story, and not think they’re here to save the scene.”

After growing up in Spain, Berger studied filmmaking at NYU. Thus Robot Dreams is filled with Berger’s own memories of New York in 1984, as well as inspirations that range from Martha Cooper’s photography to films such as Stranger than Paradise, Desperately Seeking Susan, Hannah and Her Sisters, After Hours, and Liquid Sky (“a very Dazed film – it has aliens and models!”). He also considers it the closest a movie has to come to what he envisioned in his head. “I’ve only made four films in 20 years. I love detail. I can spend so much time trying to find the perfect colour, the perfect shot.”

Even on a live-action feature, Berger notes, the most storyboarded scene still faces numerous variables. “On live-action, the director is like a clown on top of a wild bull,” he says, miming the action. “But on an animation, it’s like you’re on a horse, in control. Every shot on this film has my fingerprints. Every pupil movement, I was involved in that decision.” It was also his insistence for the film to be animated in deep focus. “I wanted the line to be alive, and in 2D. Imperfection, for me, is perfection.”

During awards season, Berger has been participating in talks and events with directors at other studios like Sony and Pixar. Over dinner, he and fellow nominees would swap anecdotes. “They had envy of the complete control I had on my film,” he says, “and I had complete envy of the budgets that they had.” Funnily enough, Blue Sky Studios (Ice Age, Spies in Disguise) held talks with Sara Varon in 2008 about potentially turning Robot Dreams into a 3D feature. I ask Berger if he can envision himself working in blockbuster animation – he has, after all, just spent months networking in LA?

“For me, what’s important is control,” says Berger. “I’ve made four films with complete freedom and final cut. I had offers [in the past] to make big-budget films in America, but I decided to make smaller films with more control.” He praises Yorgos Lanthimos and Jonathan Glazer as directors he’d emulate if he went to Hollywood. “I want to surprise the audience with my next project. It could be animation, it could be live-action, it could be a documentary. I just want to do something I haven’t done before.”

Despite Robot Dreams premiering almost a year ago, Berger still expresses excitement over the film’s gradual rollout. While doing Q&As, he’s even had viewers tell him it reminded them of a parent. “That’s what’s great about cinema,” he says. “The audience makes the film for themselves.” I admit that, on first viewing, I thought Dog and Robot were friends; the second time, the hand-holding felt romantic. “There’s a fine line between friendship and love,” he says. “What is friendship? Romance is just friendship plus sex? You don’t need sex anymore? It’s up to you how you see the film.”

Robot Dreams is exclusively in UK cinemas from March 22