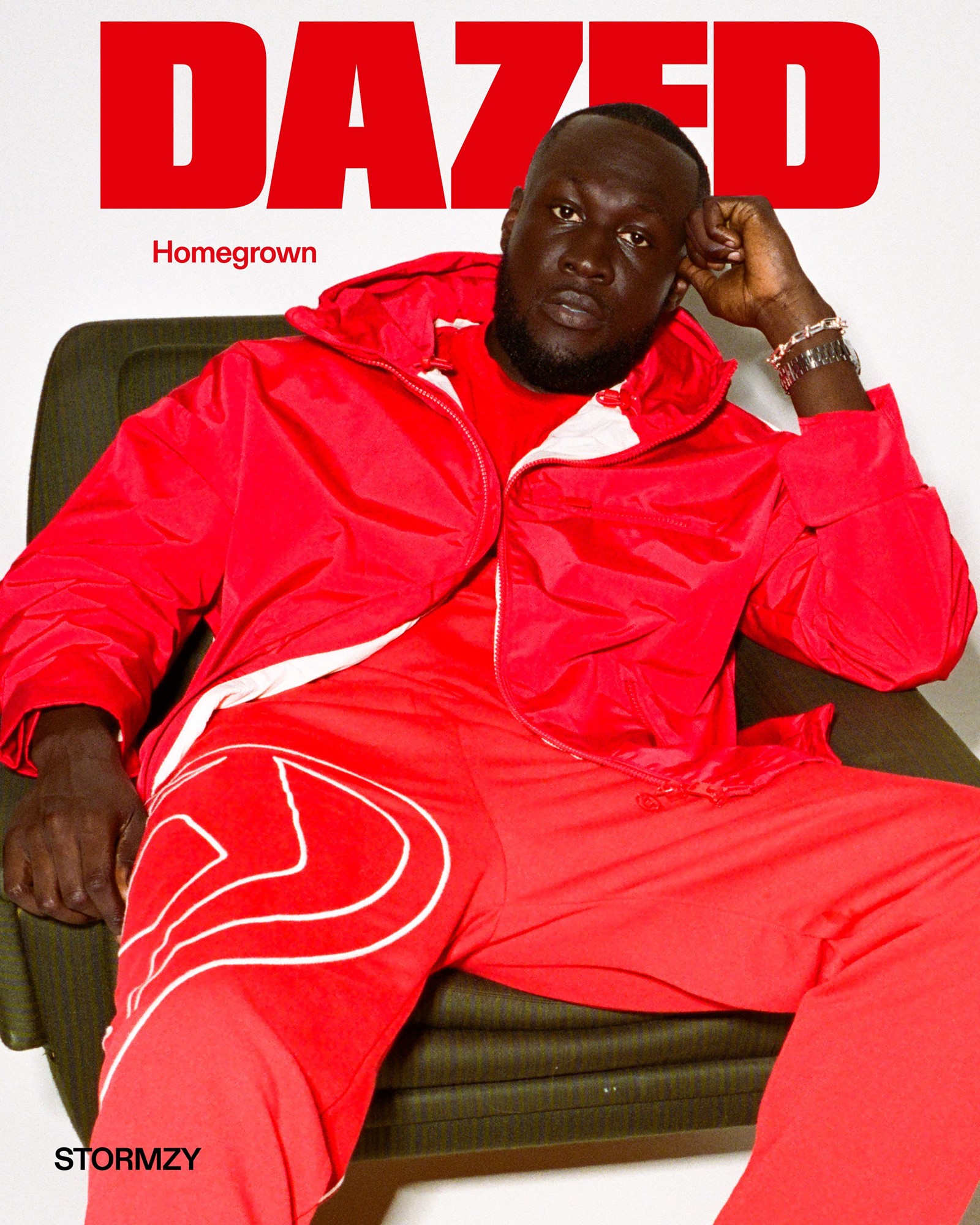

Next month, Stormzy will turn 30. July 26, this chapter will close, and out on the horizon, a new one will open. Boy becomes man, the chaos of youth firming into the full blooms of adulthood. Time comes for everyone, the tide must roll in. And soon, he will be next.

Stormzy isn’t nervous about this passover. He has been ready for 30. He feels fresh. He feels healthy and he feels sharp. Last November he released his third album, This Is What I Mean, a liberating record pulling on influences ranging from soul to rap, R&B to Afrobeats, the 12 songs teasing out his private, poignant reflections on a deepening faith, on broken relationships with fathers and ex-partners, on his mental health and more.

Today, he is sitting in a small, windowless recording room of a south London studio, reflecting on what has passed since then, and what is to come. "There’s a difference in doing music at 22 and when you’re about to turn 30,” he says. “It’s the kind of peace and stability and stillness you can only get from maturity. You lose all the nervous shivers and the anxiety; you shake it off because now you’re a grown man coming into your skin.”

A week after finishing This Is What I Mean, Stormzy was back in the studio, recording new music. It was the first time he had completed the long, intense album process with his sanity, wellness and mental stability all in check. Usually, after finishing albums, he is plagued by a heaviness, feeling mentally drained and overwhelmed. But this time he felt light, crediting the shift to God.

And so, as 30 approaches, he has new music on the horizon. He has purpose and joy. He feels relaxed. But he has questions, too: Where should I be aligned? What’s next for me?

There were things Stormzy always pictured in his future, dreams and ambitions he saw one day blooming into reality. “It’s off to the charts I go,” he said on a freestyle when he was around 18. “Come from below, then I blow like I’m due to,” he rapped on “Not That Deep”, three years later. There was something in the way God spoke to him. He felt things. He knew someday a headlining slot at Glastonbury would come to pass. There was a knowing, a sense of what was waiting out in his future. And so, he committed his dreams to faith and spirit and his God. And eventually, by work and grace and timing, they arrived.

In 2017, his debut album Gang Signs & Prayer entered at number one on the UK album charts, selling 68,594 copies in its first week, the first grime album to mount the summit. He was 23. A year later, he won British album of the year and British male solo artist at the Brits. At 25, he walked out under the beaming lights of the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury, the first Black British solo act to headline.

A young boy’s pipe dream had spiralled beyond anything he could imagine. He expected success, but never knew it would come so quickly. And so now here he is, in a windowless, south London studio, almost 30, three albums deep, millions of records sold, one of the biggest musicians in the country, waiting with questions for the same God and spirit who guided him here: Where should I be aligned? What’s next for me?

The old will be burned, and in its ashes, something new.

“All I know is that the next chapter for me includes music, but other than that?” he says, “I don’t know. It’s the most beautiful ‘I don’t know’... There’s no confusion in where I should be and who I should be. It’s like ‘God, I’m ready to do the work here on Earth, you just guide it.’”

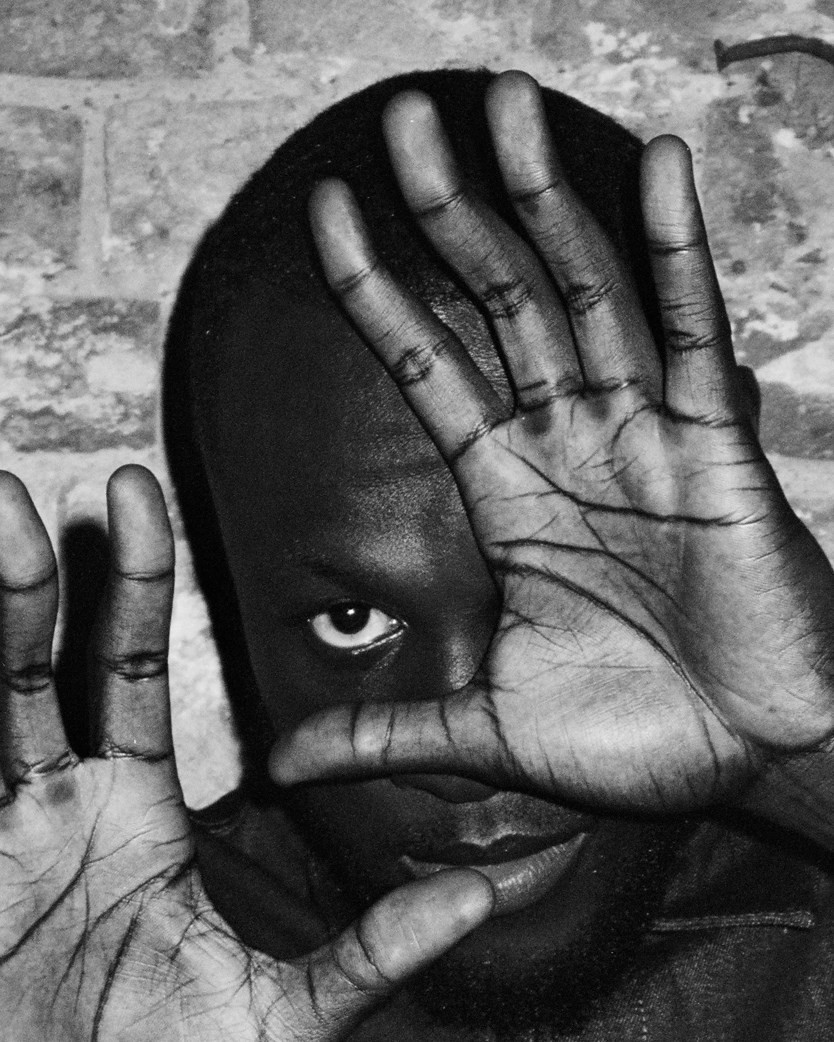

The road that led him here was paved by many hands. There are pieces of others in him. To know Michael Ebenezer Kwadjo Omari Owuo Jr you must know Croydon and south London and a generation of young people who grew under the haze of the new millennium.

Croydon rests in the deepest waters of south London, a borough boundaried with Surrey and the fringes of the rural North Downs in the south, then running inland towards the north of the borough, until the greenery yields and the dense inner-city towns of Thornton Heath, Selhurst, Norbury and South Norwood rise from the earth. Stormzy was raised in this northern half, in a section of the borough that holds one of the largest localised settlements of Black people in Britain.

Rap and music have echoed around these roads for generations. Young men and women unfurling from African and Caribbean ancestral lines, tumbling out into deep south London, using a 16-bar to set their joys and sorrows into stone. His generation inherited this tradition. They came of age in a time when grime and UK rap had descended out of garage and dancehall and hip hop, and the urge to MC on a street corner, in the town centre, on the back of a bus was as natural as drawing breath. “Man was listening to just bare UK,” he says, “just British music.”

The music was woven into the social climate. The northern half of Croydon had long wrestled with alarming levels of deprivation and inequality, of child poverty and low income, and a serious youth violence crisis sweeping through the inner city, claiming the young. In south London, UK rap and grime spoke to the same fragility that birthed it, his generation clinging to the music that surfaced in the fallout of these extremes. There are melodic jewels from this time that echoed through Croydon; the ruggedness of the ‘gangsta grime’ collective Roadside G’s, or the poetic pleading of a song like “Cry” by Swiss of So Solid Crew, whose tender and mournful surveying of the human condition in south London spoke to the collective Black soul.

“There’s no confusion in where I should be and who I should be. It’s like ‘God, I’m ready to do the work here on Earth, you just guide it’” – Stormzy

Stormzy grew up in Norbury with his mum, his two sisters and his brother. His mum worked two or three jobs. He remembers how she would come home in the afternoon from a shift, make a corned beef sandwich, put the kettle on, sit in front of the TV for a little while, then pull her trainers on and head straight out again for her next job.

And so, he was an outside kid. Some days he’d be out in Norbury or Thornton Heath, on the roadsides with his friends when somebody would put on an instrumental, and they would all start rapping. “It wasn’t even as deep as ‘music’ yet, man just loved to spit... to fuck up the riddim,” says Stormzy. “Man has to come with man’s 16-bar and fuck the place up and say some slick shit.”

In these first flirtations with music are the traces of who he would become. On a song with another local MC, Weazy, a budding artistry slowly begins to find form. He’s in his early to mid-teens, his voice high, his flow aggressive as he paces through punchlines: “Bullets will cover man / If I don’t drop him with the first then I’ll give him another bang.” They were teenagers MCing about what they knew, posturing with exaggerated lyrical threats and speaking on the goings-on in their own small corner of the city, the local roads of home their only reference point before the world showed them anything else.

As boys, they would rove to other areas of the borough, chilling with other groups, “getting up to whatever” and battling the other anointed spitters from around the way. It was in these earliest arenas, with his first audiences, where he began to realise he had a gift, where he would hear the gathered crowd react with an “ohhhh” or a “bap-bap-bap!” whenever he unveiled his 16 or 32-bar freestyle.

There was a hierarchy in the ends. When Stormzy was in school, the rappers and MCs a few years older than him were local celebrities, kids like Krept, Konan, Cadet, Sayper, Drives and Charmz who gained early hood fame. Charmz – Carl Beatson Asiedu – was one of the top boys, an MC Stormzy admired (“The hardest, and witty, clever, sick, funny”). He was a dreamer who would go on to have an early breakout funky house anthem titled “Buy Out Da Bar”. One day, when out on the ends, Stormzy was around when Charmz was spitting with friends. He joined in. The two started going back-to-back. Charmz, impressed by what he’d heard, bestowed on Stormzy the tag ‘Younger Charmz’.

In south London and across Britain’s inner cities, tags were used in place of government names. They were the marker your local community knew you by, your first assertions of self to your own small world. A ‘younger’ version of you was then crowned on a little sibling, cousin or friend, a piece of you passed on to somebody you saw yourself in. Sometimes a ‘Younger’ would then pass the tag on to a ‘Tiny’, a ‘Tiny’ on to a ‘Baby’, the name handed down the generations. Gaining the title ‘Younger Charmz’ was “like a badge of honour,” Stormzy says. “He was the best in man’s area.”

Stormzy’s life and career are scattered with small memories like this, moments that made a dream possible, boys who came before, handing down a rope so he could climb. Many of those kids gave up rap and grime long ago. Some stuck with it. Others never made it to 30, lives lost to a dangerous time in south London. His music remembers them, remembers those who never crossed the threshold into full adulthood, remembers the nervous chapter in British history they emerged from.

Charmz passed in 2009, fatally stabbed after a club performance in Kennington. They played “Cry” by Swiss at his funeral. Stormzy references him on “Don’t Cry for Me” from his first album (“Now I’m just picturing Charmz all dressed in white / On the steps with Christ”). At Glastonbury he paid tribute to his friend Cadet, who died in a car crash in 2019. By these works they live on, cast in bronze on his records, the pieces of others now resting in him.

“The greatest music on Earth is coming out of Africa. Even that is just inspiring: be your Black self. And look! It’s got the world on fire. I’ll tell my kids I was a part of this time in culture. I had an offering. I was here; I was a part of it” – Stormzy

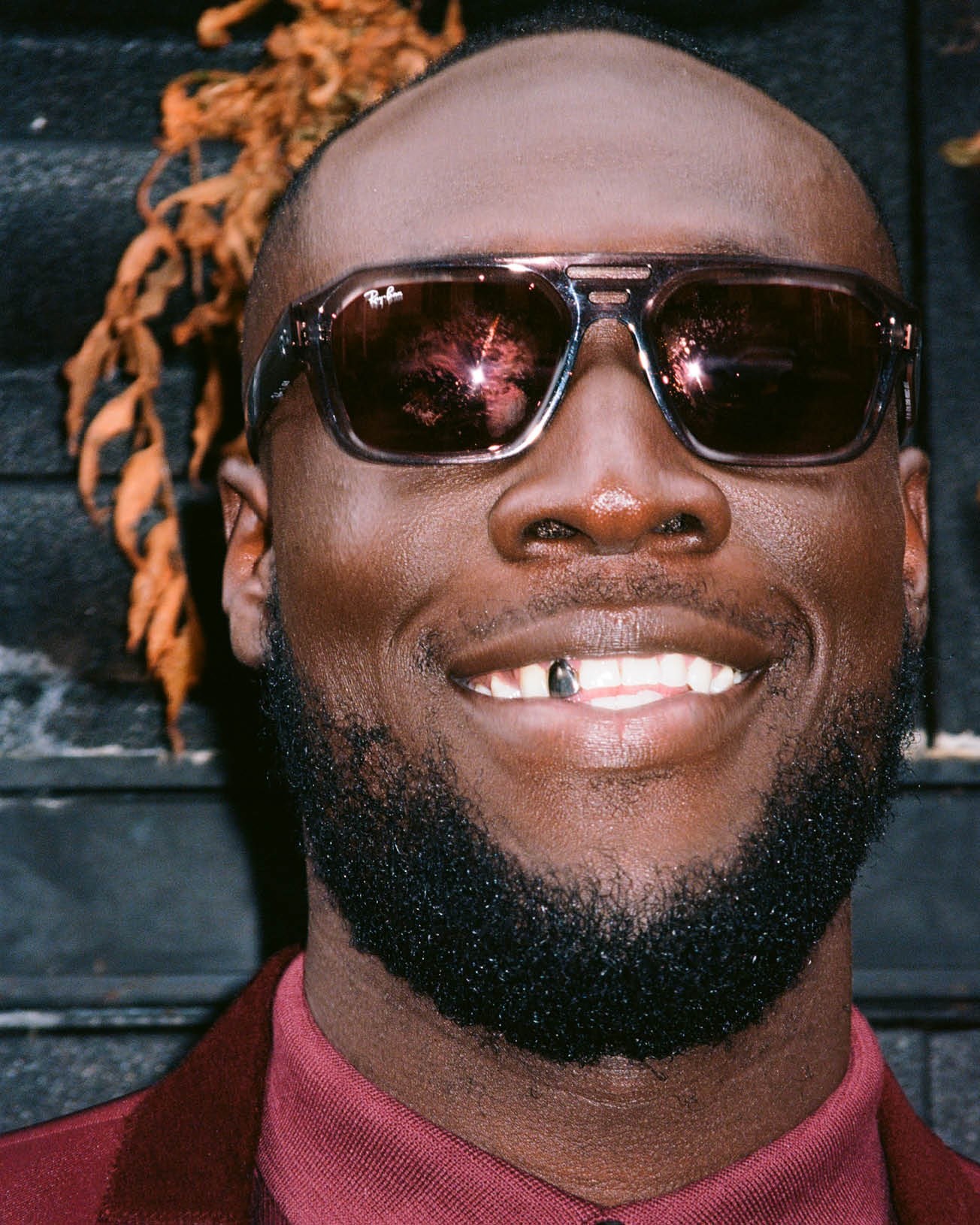

The road that led him here began before south London. Stormzy stands at a vanguard. He is not alone. In the past decade, sounds from across the Black and African diaspora have pushed out from localised music scenes, rising in a choral union to pierce the heart of global, mainstream pop culture. Afrobeats has rumbled out from Ghana and Nigeria, UK rap from Britain, Afro-trap in France, drill from Chicago, London and New York, amapiano from South Africa, dancehall in Jamaica. Black communities, separated by landmass and water, their bonds broken by the residues of colonisation and slavery, have found their way back to each other in sound.

Stormzy is a part of this. In recent years he has collaborated with Ghanaian drill artist Yaw Tog; vocalist Aya Nakamura hailing from France by way of Mali; Burna Boy from Port Harcourt, Nigeria; the singer Tems from Lagos, Nigeria and dancehall artist Stylo G from Spanish Town, Jamaica by way of south London, among others.

During a crucial scene in last year’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, a film that has become a regular meeting point for the Black diaspora, actors by way of Guyana and London, Trinidad and New York, Zimbabwe and Iowa, Kenya and Mexico move across the screen. Stormzy’s vocals guide them, his song “Interlude” soundtracking the moment. In this golden era, his fingerprints are present.

“People are just being unapologetic in their Blackness and it’s the greatest music on Earth right now,” he says about this moment in history. “The greatest music on Earth is coming out of Africa. Even that is just inspiring: be your Black self. And look! It’s got the world on fire. I’ll tell my kids I was a part of this time in culture. I had an offering. I was here; I was a part of it.”

Stormzy’s presence reflects the rooting of a distinct Ghanaian and west African presence in Britain, and the unique form it took once settled. In the late 70s and early 80s, Ghana was a country reckoning with political instability and economic decline. Unemployment was high. Subsidies on social services like health, transport and education were withdrawn, and a young generation began leaving the country in search of better horizons, settling across North America and Europe.

By the 1990s, estimates suggested that around 10-20 per cent of Ghana’s population of 20 million people were living abroad, joined by immigrants from other African countries such as Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya, some of whose economies were suffering a similar fate. Places like Croydon were a centre point of these new communities, who then birthed a generation of African kids native to Britain. Stormzy was one of these kids.

His family line reaches back to the Nungua Barrier in the Greater Accra Region. He was a baby when he first went to Ghana. As he got older, his mum would take them in the summer holidays and, despite their protests, they would be there for weeks. “We wanted to be on the ends with all the madmen doing stupidness,” he says, “but our parents just wanted to go home. That’s what Ghana was for man.”

As he got older and continued to visit, Stormzy’s relationship with the country deepened. “You just understand everything goes back full circle,” he says. “You get it, like that’s home innit; that’s home, bruv.”

“We wanted to be on the ends with all the madmen doing stupidness, but our parents just wanted to go home. That’s what Ghana was for man” – Stormzy

This blending of Black Britain and west Africa, south London and Ghana has shaped him. It’s why he can be nominated by Croydon council for the freedom of the borough award as he was in March, and then, when in Accra for the Global Citizen Festival last September, can say of the country, “It’s in my blood. It’s in my people. It’s in my home.” To be born in his part of Britain is to walk with two worlds inside you.

He holds south London, his birthplace with him. But he holds Ghana and Africa too. The stories of his mum, and those who nurtured his generation of African kids native to Britain, live through him. My own mother gets excited when she sees him on TV. They are proud of him as if he is their own, an illustration of their journey into an unknown, proof that their gamble to make their lives in foreign lands was not in vain. Through him and their children, that generation of African migrants who for so long toiled away in the quiet corners of Britain are finally seen.

Next month, Stormzy will turn 30. His sound has evolved since the block cyphers, and the first album they led to. The raps are more polished, more elaborate, his flows more refined. But there are similarities, too. The joy of recording is still there, the feeling of gathering in the studio and guiding a song or a lyric out from the ether still igniting his spirit. If ever a time comes when it doesn’t, he’ll stop altogether. On record he continues to reach inwards, searching himself and his emotions. And sometimes, when the calling is there, he sings.

“I think now even creatively nothing has changed,” he says. “I think maybe now I’m even bolder, and I’m even braver, and I’m even more fearless. But I’ve always been that... I’m all those things but with maturity.”

In the studio, he plays me a new song, rap and vocals echoing round the room. He sits quietly, head slowly bouncing to the knock of the bass as his voice booms from the speakers. The record leans into more traditional rap than This Is What I Mean. There are the twisting flow patterns, and punchlines reminiscent of “Mel Made Me Do It”, his single from last year. There is a swagger and a confidence in his tone, the ease of a man who has been rapping for more than half of his life now.

He feels some will receive his new music as an auto-correction after the tenderness of This Is What I Mean, a pendulum swinging back from the edge. But for him, the span of sounds feels instinctive, the many faces of his artistry showing themselves in a range of tones and genres.

“This artist and the artist who made Gang Signs & Prayer are so different, but they are exactly the fucking same,” he says. “GS&P Stormz and 2023 Stormz, neither of them gives a fuck about pleasing someone’s appetite. Not in an ignorant way, [but] because it’s coming from a real, genuine place in [my] spirit.”

This is who he is as 30 approaches, as one chapter closes out and another opens. He feels rooted. He feels free.

Aniefiok Ekpoudom’s book Where We Come From: Rap, Home and Hope in Modern Britain is out in January 2024 via Faber & Faber

Grooming BIANCA SIMONE, tailor MAJULA LAITINEN, photographic assistant CONNOR TEGAN, styling assistants KENNEDY CLARKE, LARA MCGRATH, QASIM ISAH, production YMI STUDIO, production assistants HELENE SELAM KLEIH, ANNA WINTER