In an era where almost everything is sexually permitted, and shock has been supplanted by outrage, taboo has lost its potency on the runway

This article is part of our Future of Sex season – a series of features investigating the future of sex, relationships, dating, sex work and sex worker rights; tech; taboos; and the next socio-political sexual frontiers.

The only image to appear on the invitation was that of human flesh. A pale wound haphazardly sewn back together with bits of string, as if it were the handiwork of a backstreet surgeon or an act of self-mutilation. That piece of card would be the prelude to 30 minutes of psychic romance, where women staggered through a catwalk strewn with heather and bracken, eyes glaring from beneath alabaster contacts as clanging bells and thunder crashed overhead. Many of them barely adult, their bodies were exposed in clawed lace, leather bumsters, and dresses that had been slashed at the breast, as Alexander McQueen stuck his fingers into the fissures of consent.

Though it only served to cement his preeminence in culture, when Highland Rape emerged on the runway in 1995, it was met with immediate revulsion by the British press, who took the collection as a degrading attack on women. “It is McQueen’s brand of misogynistic absurdity that gives fashion a bad name,” read a line in Sally Brampton’s review in The Guardian, while Marion Hume and Tamsin Blanchard at The Independent labelled the show “an insult to women and to his talent.” Needless to say, McQueen refused to give oxygen to those criticisms, making it known that Highland Rape was a metaphor for England’s pillaging of Scotland in the 18th century. “I can’t compensate for a lack of intelligence, but I wish people would try a bit harder,” he told The Sunday Times in 1996. But it was about rape, and it was deliberately ambiguous, with McQueen wringing his own memories of assault onto clothing that stirred deep and gruesome fascinations.

Throughout his career, McQueen sublimated suffering into uniquely powerful works of art, rebelling against a fashion system that was just beginning to lose its power to overwhelm. By tearing the most potent of taboos asunder – like sexual violence, death, disability, and mental illness – his collections rarely reached an ethical resolve; and nor were they meant to. Much like Vivienne Westwood’s swastika t-shirts, Jean Paul Gaultier’s menswear skirts, and Hussein Chalayan’s burqas, which rendered models completely nude below the navel, McQueen thrust disturbing imagery into the public’s face, evoking nuanced conversations on gender, power and vulnerability through sheer trauma and provocation. In comparison to Highland Rape, more recent attempts to address sexual autonomy have been reduced to slogans, with Maria Grazia Chiruri printing the word “consent” onto a white t-shirt and Alessandro Michele embroidering the back of a suit jacket with “my body my choice”.

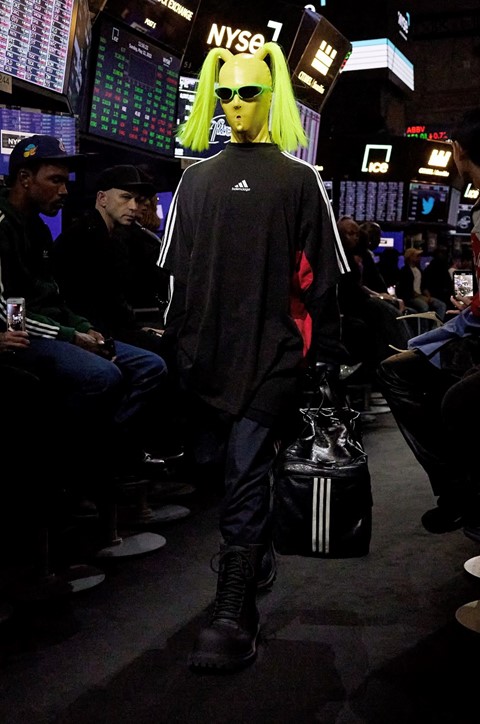

As the sans-serif lettering of those pieces makes clear, fashion’s relationship with sex has never been so plain. Throughout the SS22 season, journalists hawked the runway’s so-called “return of sex” and publications continue to blether on about how designers are in their “slut-era”, on account of the way in which brands still use sex to garner attention. But when the naked body is as ubiquitous – and available – as has been suggested, it loses its libidinal charge. Low-slung trousers are not arousing in the same way that McQueen’s bumsters were, for example, which felt disobedient and wrong. To inspire the erotic, there needs to be an element of the perverse, something transgressive to titillate and surprise, lest it ends up being superficial. In an era of supposed liberation – where pay pigs and Cock Destroyers have become online gaffes – sex has converged with entertainment. Look at Ludovic de Saint Sernin’s PornHub collaboration, Frank Ocean’s cock ring, Julia Fox’s mons pubis trousers, the gimps at Balenciaga, buttplug accessories at Gucci, and the numerous Tom of Finland collaborations.

While perhaps fun, none of this is nearly as subversive as it’s made out to be. In a society where almost everything is permitted – particularly sexually – owning a t-shirt emblazoned with a mammoth cartoon phallus brimming with sap isn’t as shock-inducing as it once was. That’s by and large a good thing, of course, but the disappearance of taboo also coincides with the disappearance of the most psychologically complex fashion designers. “You’ve got nothing to kick against! The purpose of taboo is shock-busting. It’s a talking point,” Judith Watt, fashion historian and the author of Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy says. “And it just captures the zeitgeist. You look at it and think: ‘Why do I feel like crying?’, ‘Why is this so fucking incredible?’” By inhabiting the kind of ideas that would otherwise lead to social ostracisation, taboo actively moves culture forward, bringing ambiguity to some of our most firmly held beliefs. And, in fashion terms, “everything that comes after looks outdated.”

As images of bygone runways are endlessly recycled on archive Instagram accounts and High Fashion Twitter, we tend to lose sight of just how radical designers like McQueen really were. Watt connects this to the arrival of codpiece in the 16th century, when aristocrats walked around with swollen protuberances bursting from their velveteen breeches. “It was disgusting. Clothes had to be modest, so God forbid you committed the sin of vanity. You see, taboos were much smaller then, we’ve just broken most of them.” That being said, to bear witness to anyone wearing a codpiece outside the boundaries of a fetish club – say, in a supermarket or at a funeral – would still be a violation of norms. In contrast, when a man with a hooked appendage walked Thom Browne’s SS23 runway in New York, it was not a moment of dissent, but of whoops and cheers, as the model tipped his cowboy hat in time with a Madonna song. “There’s nothing less taboo than mainstream fashion, it’s so bland,” Watt says.

Obviously, not all taboos have been absorbed into pop culture. As Watt asks me, “are you going to have sex with your mother or not? Am I going to have sex with my Dachshunds? Now THAT’S taboo, darling.” But we have reached a point where even the Benetton adverts of the 90s – those depicting AIDs deaths, human bones, and amputees with spoon-arm-prosthetics – would make an unlikely fashion billboard. “We’re living in a time when people find things offensive, but life is offensive,” she says, with a sigh. That’s not some clarion call to end woke culture – we are, after all, living in a society structured around a suffering class – but it’s testament to the limits it has placed on designers, and the way outrage has supplanted shock. As John Waters said to Dazed earlier this year, “there’s even more rules today, especially in the world of the arts.” And it’s not like we’re experiencing a sexual utopia, either: technology has calcified some of the most regressive views surrounding sex. Nipples are censored, fat people are shadow-banned, and even McQueen’s runway videos come with an “inappropriate for some viewers” YouTube warning.

That’s not to mention the rollback of Roe v Wade, mounting hate crimes against LGBTQ+ people, and a swell of anti-trans rhetoric. All of which just makes it more surprising that more designers don’t feel more embattled to stare down the barrel of taboo. Perhaps one person who managed to do that last season was Mowalola, whose SS23 collection featured balaclava dresses that forced the wearer’s arms into uncomfortable submission. To make a comparison to McQueen is trite, but Mowalola’s burglary of the body chimed with Rebecca Arnold’s description of the late designer, who approached sexuality as a site of conflict, “where frustration and anger is inscribed on the skin in contradictory images of anguish and pleasure.” But this is rare. Today, the most popular designers trade in obvious statements, and since nothing can represent anything other than what it really is, they make their stance on taboo subjects painfully legible. Not unlike that “why be racist, sexist, homophobic, or transphobic, when you could just be quiet” t-shirt that sometimes gets regurgitated on social media.

Will fashion ever be taboo again? Watt is equivocal in her answer: “Not on the runway.” In real life, it’s much easier for clothing to cross social fault lines, but contemporary culture has proven that being shocking isn’t tantamount to being a good artist. There’s a reason why McQueen’s work continues to hit the nervous system – the image of Shalom Harlow twirling in ecstasy as mechanical arms splatter her in paint, or a nude Michelle Olley reclining on the moth-eaten carcass of a chaise longue, her preternatural head bowed and attached to a breathing tube – and that’s because he understood that society’s psyche was just as fragile and disturbed as his own. There will always be social problems, but without taboo, art becomes formulaic, and without taboo, fashion cannot be art.