Nüwa is set to be ready for human residents in 2100 – here, its architect explains who it’s for, how it may resemble pandemic life, and how it might actually help us on Planet Earth

Welcome to A Future World – Dazed's network, community, and platform focusing on the intersection of science, technology and pop culture. Throughout April, we're featuring conversations and mission statements from the people paving new pathways for our planet: activists, inventors, fashion pioneers, technologists, AI scientists, and global youth movements, alongside in-depth editorial exploring the new realities for our future world.

What will life be like in 100 years? Some believe civilisation will be wiped out before then, while others are preparing to upload their brains to the internet, live until they’re 1,000 years old, or identify as cyborgs – that is, if they even remain on Earth.

Meanwhile, 270 million kilometres away, a new city will be blossoming. Inside a rock on a steep cliff on Mars, humans will be working, eating, socialising, and shopping. Each morning, they’ll wake in their excavated domes, catch an intricate network of lifts to wherever they’re going – an artificial park, a football match, the hospital – and look out onto the red desert below. These will be the residents of Nüwa, the first self-sustainable city on Mars. And, if all goes to plan, they’ll be arriving on the planet in just 80 years.

“Humans are explorers,” says Alfredo Muñoz, the founder of architecture studio ABIBOO, the brains behind Nüwa. “Going to another planet is an opportunity for humans to thrive, and to potentially survive.”

The blueprint and design of Nüwa was a collaboration between ABIBOO and SONet (The Sustainable Offworld Network) for a competition by The Mars Society. Entrants were asked to design a Mars city state which could house one million people, and Nüwa was one of 10 finalists out of 175 entries.

“The idea was to create not just a base where a lot of science can be supported,” explains Mars Society president Robert Zubrin, “but to create a society which will only grow if people want to live there.”

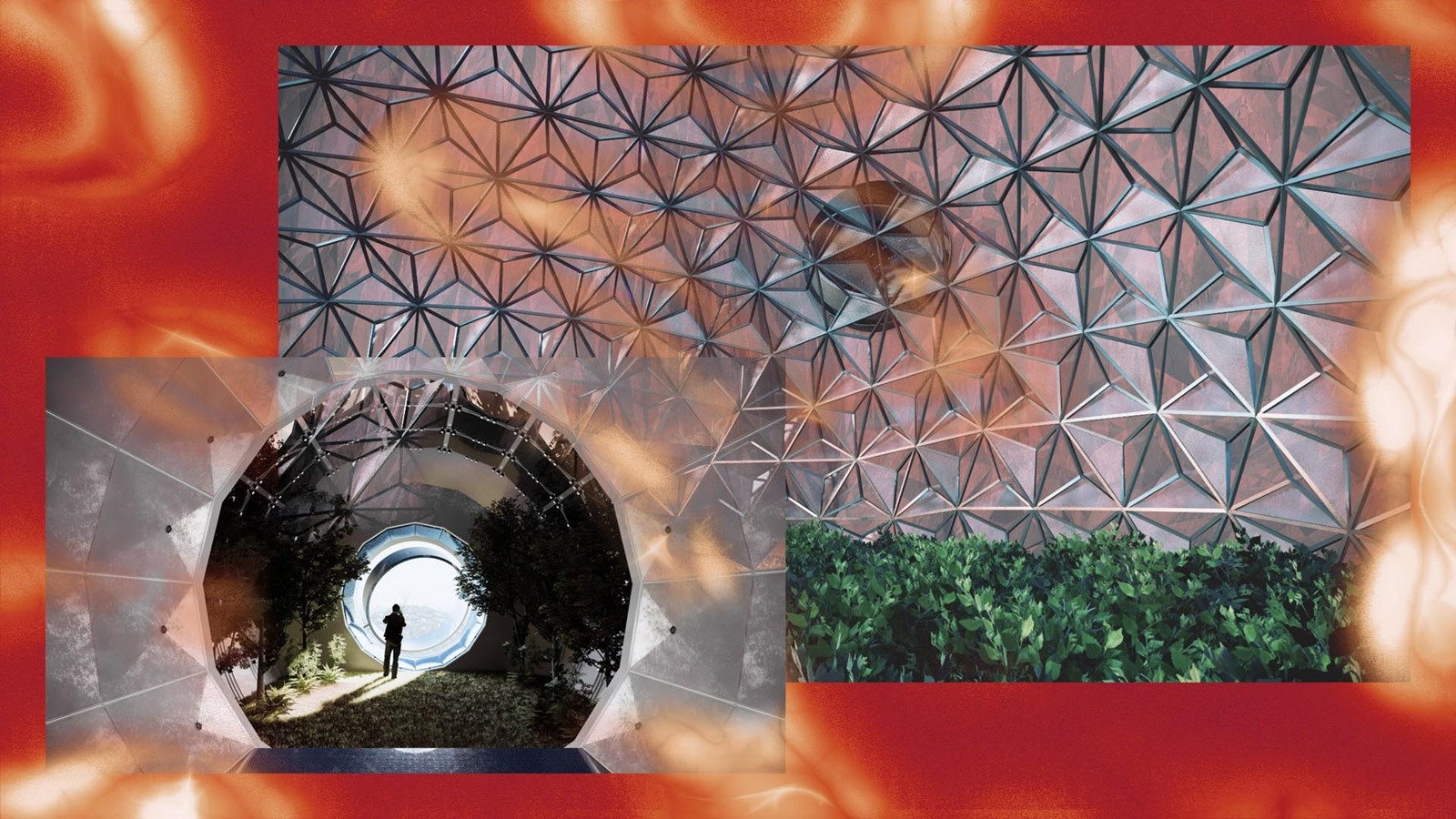

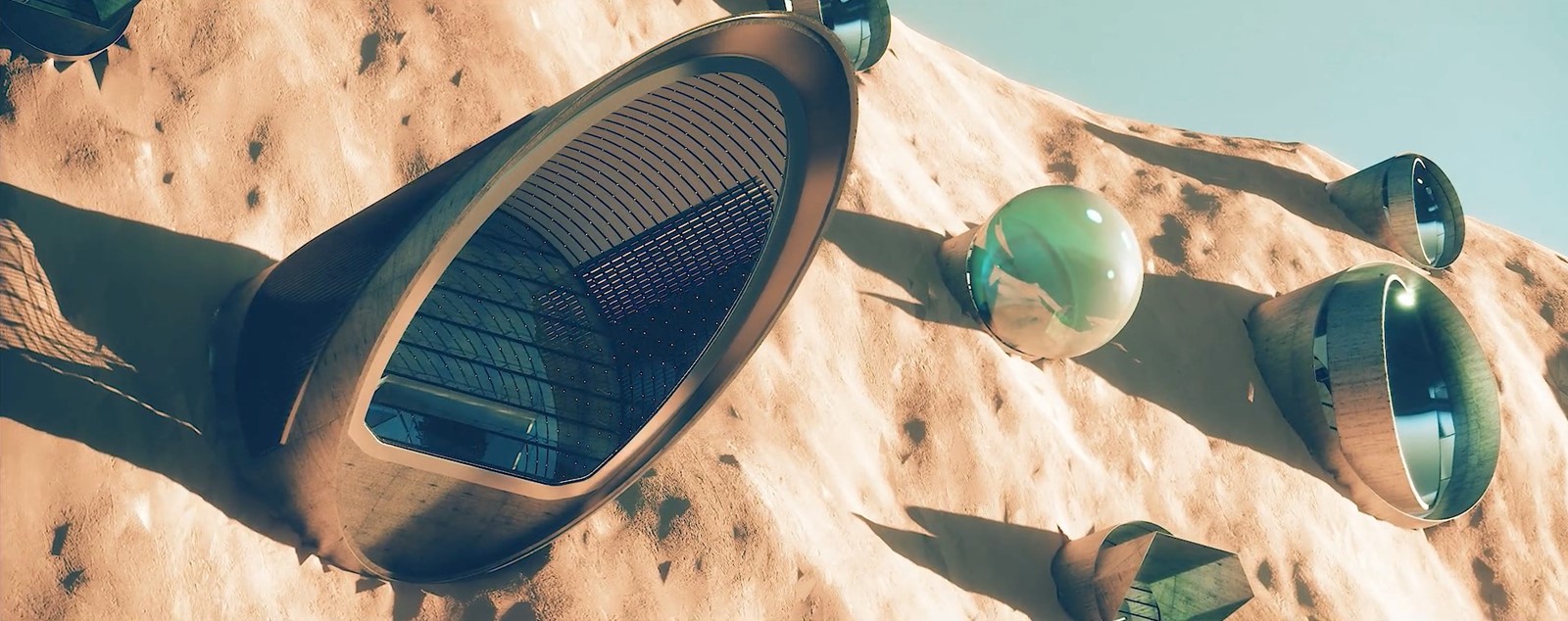

Just looking at Nüwa, you probably would want to live there. The city overlooks Mars’ vast expanse of rust-coloured sand, which can be admired from spacious teal and silver orbs that jut out from the edge of the cliff. Known as ‘Green Spaces’, these orbs boast swimming pools, grass, and towering trees, and act as nature spaces for residents whose lives will be spent indoors. Further inside the cliff are the more brutalist ‘Macro Buildings’, which offer hotel-esque residential quarters, pink-hued office spaces, and formidable art domes.

A high-speed elevator system connects these buildings to other areas of the rock. Right at the top is the ‘Mesa’, where manufacturing, energy generation, and food production takes place. Head to the bottom of the rock and you’ll find the ‘Valley’, where you can socialise, shop, and attend school or university. This area will also be home to farming spaces, as well as train stations which communicate with the space shuttle.

“What we have done so far is a preliminary approach about how we envision Nüwa,” Muñoz tells me over Zoom, his background placing him inside one of the city’s swanky office spaces. “There will be a lot more simulation that needs to be done on the technical, engineering, and even architectural aspects.”

“The amount of mobility that we’ll have on Mars will be completely different to our normal life on Earth, because if we go out on Mars, we die” – Alfredo Muñoz, ABIBOO architecture studio

Although it took 35 people less than a year to create, Muñoz asserts that designing for a planet you’ve never been to isn’t easy. “In architecture and urban planning, the first thing we do is go to a site and explore,” he explains, “but here we could not do it.” Instead, the team relied on “3D software, sketches, and models” to visualise how they thought the space would be. But, unlike designing for a city on Earth, Muñoz and his team had only unknown resources at their disposal. “We did a lot of work with engineers and scientists to identify what materials could be available on Mars, and which of the materials we originally wanted to use – based on our expertise here on Earth – would not be feasible or would be too expensive to obtain.”

Another key hurdle was how to protect Nüwa’s residents from the various dangers that Mars poses to humans. “By going inside of a cliff, we were able to solve the problem of radiation and (protect against) potential impact from meteorites,” Muñoz reveals. “Also, the buildings have a lot of pressure inside, so if we were to go outside where it’s almost zero atmosphere pressure, the buildings would try to explode. But because they’re inside a rock, the rock absorbs that pressure.”

One design aspect that Muñoz is particularly pleased with is the ‘translucent skins’ that surround the ‘Valley’ building and offer residents their only chance to fully immerse themselves in the landscape of Mars. “The problem that we have on Mars is that a transparent material doesn’t provide protection from radiation, which is basically lethal,” he says. To combat this, the excavated material from the cliff will be, as Muñoz says, “dumped” on top of the ‘Valley’. “This gives you protection but also creates a beautiful relationship with the Martian landscape.”

With the ever-present risk of radiation, meteorites, and nearly no atmospheric pressure, it seems life on Mars won’t be a walk in the park. “We did some analysis about the amount of energy that would be required on Mars,” says Muñoz, “and per person, it will be around 10 times more than the amount of energy we need on Earth. Obviously we can’t work 10 times more, so we’ll rely on artificial intelligence and effective systems and robotics, but it will be a very intense lifestyle. It’s not about going to Mars to retire or go on holiday.”

Muñoz emphasises that those who do choose to settle in Nüwa will be required to have jobs, with their contracts signing away 60 to 80 per cent of their work life to tasks assigned by the city. “Most of the work will be related to technical and management tasks associated with the city’s operations, mining, and production of food, goods, and energy,” he explains. “Although robotics and artificial intelligence will perform the most intensive work, such technology will need to be co-ordinated and managed correctly.” Muñoz asserts that arts and self-expression will also be “a critical aspect of society and life in Nüwa”.

As the journey to Mars will take one to three months, and with the shuttle only set to travel to Earth every 26 months, it’s likely that most people who make the trip will only do it once. But, with tickets set to cost a cool $300,000 (£218k), it’s unclear who the city of Nüwa is actually for. “I would like to clarify that $300k was an estimate that was done on an academic level,” states Muñoz. “There is still a lot of work to be done in order to get a clear understanding of what the price will be and when we can actually go.” What has been decided, however, is what residents will get for their money. As well as a one-way ticket, Mars settlers will get a residential unit, access to common facilities, life support services, and food. Each resident will also get a Mars City Share (MCS) on arrival, which means they’ll gain profit as the city develops.

When it comes to political and economic systems, although Muñoz says Nüwa will require “a community that is very reliant on each other”, it appears more capitalist elements will remain. “We envision a system that will combine the private sector – we’ll have our own economy and currency that will incentivise entrepreneurship – and, at the same time, ensure that there are no extreme differences (between residents).”

“The only way we will be able to survive on Mars is to transcend who we are as a species” – Alfredo Muñoz, ABIBOO architecture studio

Despite most elements of Earth’s broken society probably being implemented on Mars, Zubrin says life there will offer “an arena of free experimentation”. He adds: “There will always be people who’ll have new ideas on how society should be organised, and who’ll want to go to a place where they can cut their own path and make their own world, and who’ll be willing to accept a significant amount of hardship in order to do that.”

Work and politics aside, Muñoz admits that day-to-day life in the city will resemble “how we’ve been forced to live during COVID”. He explains: “The amount of mobility that we’ll have on Mars will be completely different to our normal life on Earth, because if we go out on Mars, we die. But instead of being forced to live this way (like we have been during the pandemic), we are working around it, and saying, ‘OK, what do we need so we can be happy living most of the time in a building?’.”

Although it will be hard work, Muñoz believes it will be worth it for those who are brave enough to go. “For humans to settle on another planet will be a milestone in the history of humankind – you’ll be a part of an experience that’s not only about the adventure, but also about self-growth. The only way we will be able to survive on Mars is to transcend who we are as a species.”

As our species is currently at risk of making itself extinct, questions have been raised about whether Nüwa and other Mars settlement proposals are less about exploration and more about escaping a soon-to-be inhabitable environment on Earth. “It’s not about finding a plan B,” Muñoz explains. “The beautiful part is that by solving a settlement on Mars, we’re learning so much about technologies, strategies, and solutions that can be implemented on Earth. Sometimes when you look at a problem with completely different eyes and you’re forced to think outside of the box, you start to come up with solutions and ideas that you didn’t think of before.”

Zubrin insists settlement on Mars won’t mean we’re “abandoning the Earth” because “even if you had 100 one million-person Mars colonies, that’s still only 100 million people, which is very small compared with the population of the Earth”. He says it’s instead about “creating new societies with their own creative potentials that will add to the creative strength of the human species”.

But, says Muñoz, keeping civilisation alive after self-destruction on Earth is “a reality too”. In this sense, humans would have to learn a lot of lessons if they were to see Mars as a second chance. “The Martians are going to face many challenges on the frontier,” explains Zubrin. “They’re going to have to develop super productive greenhouse agriculture, so they’ll have to engage in genetic engineering to create super productive plants. The Martians will need energy, and there aren’t fossil fuels or waterfalls on Mars, and solar energy is only 40 per cent as strong as it is on Earth, so they’ll develop fusion power. All of these inventions will benefit the Earth.”

Though this all sounds a bit too futuristic for the next 30 years – Nüwa is slated for construction in 2054 – Zubrin is hopeful it could happen. “It’s hard to know what the world’s going to look like,” he says, “but if we have people on Mars in the 2030 timeframe, I could see us having hundreds of people there by mid-century, so it could be possible that we’ll have a million people on Mars by the end of the century.”

Elon Musk (who didn’t consult on this project) is already planning on sending humans to Mars by 2026, which may enable a good 70 years of exploration before the 2100 move-in date. “Nobody has been there to do any geotechnical analysis,” says Muñoz, “so we believe that the preliminary settlements, and Elon Musk being the visionary behind that very aggressive agenda, could definitely be critical to actually get those on-the-ground learnings and information that will help with our engineering of Nüwa.”

So, will Mars be nicer than Earth? “I doubt it,” the extra-terrestrial architect admits. “We have such a beautiful place on Earth, so it’s impossible to create somewhere better than here.”